The Battle of Kursk

Chapter 24

“The tanks reached the trench line and, with a terrible roar, clattered overhead”

5 July - 23 August, 1943

Waffen SS Panther tanks in action at Kursk

German Federal Archives

Still smarting from the disaster at Stalingrad, the Wehrmacht was now poised to strike at the Soviets in their grand summer offensive of 1943. Operation Citadel was targeted at the Soviet salient in the lines near Kursk, with the Germans massing their newest, best armor along with vast quantities of aircraft and men for the operation. Desite these plans, the Soviets were also preparing for an offensive, also targeted at Kursk. Hoping to allow the Germans to wear themselves out, they planned a massive counteroffensive to break the Eastern Front open and begin pushing the Germans westward in earnest.

A convoy of German trucks heads toward the lines before Operation Citadel

German Federal Archives

Preparations for Operation Citadel had commenced immediately after the German victory at Kharkov. The German counteroffensive in the wake of the disaster at Stalingrad had seen both the Red Army and the Wehrmacht exhausted, and both had elected to wait out the spring mud season and build up their forces.

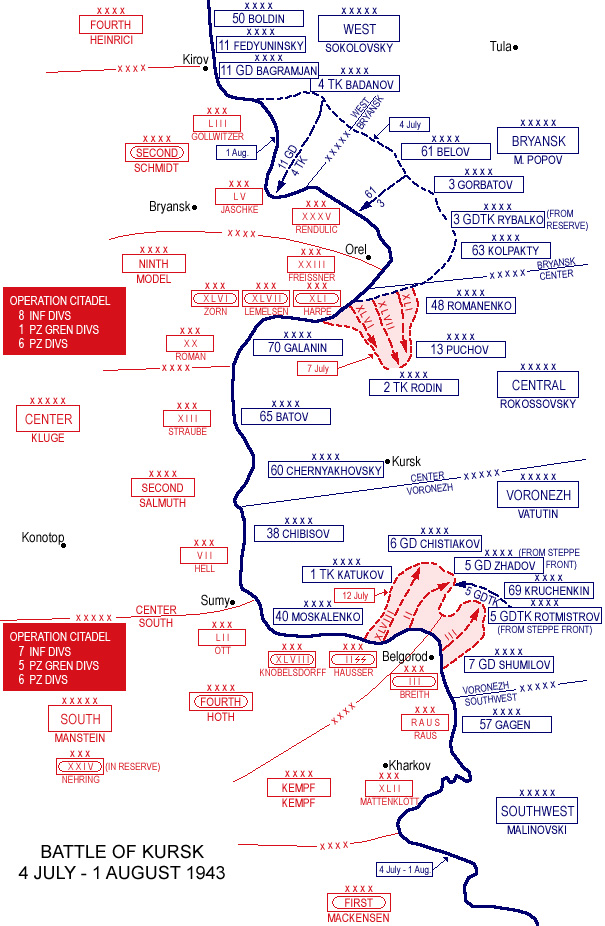

The German plan for Operation Citadel was, in essence, the same maneuver that had won them their great victories in the previous two summers in the east. They would strike at the Kursk Salient (which was approximately 155 miles from north to south) with two Field Armies from Army Group Center and Army Group South along with supporting units, cutting off the salient and allowing the destruction of the Soviet forces inside it before the advance eastward resumed.

Senior Soviet leadership at Kursk, with General Ivan Konev (center) speaking to Marshal Zhukov (right)

The Soviets, however, had no intention of allowing the same result again. Significant forces were being concentrated in and around the salient, and fortifications were under construction. The VVS (the Soviet Red Air Force) had finally begun to recover its strength after its near annihilation during Operation Barbarossa, with increasing numbers of veteran pilots available to operate newer and more effective machines. On the ground, Soviet intelligence had noted the Germans massing around Kharkov and Orel, and the Red Army was massing a force of some 2.5 million in three Fronts to meet the offensive.

A German Feldgendarme (MP) directs traffic as troops move up to the front at Kursk

German Federal Archives

The upcoming operation had been a source of some contention in both the OKW and the Stavka. At his headquarters in Rastenburg, East Prussia, Hitler was in two minds about the planned attack, with his aggressive nature at odds with the advice of some of his most trusted leaders that it was prudent to postpone or cancel the operation, leaving the Fuhrer conflicted. In Moscow, Stalin had pressed the Stavka to launch an attack before the Germans had, but had eventually been tempered by his military leaders. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the deputy to Stalin as Supreme Commander, had argued successfully to wait, first absorbing the German blows and then parrying against the now exhausted enemy with the huge Soviet forces left in reserve.

A battery of German Wespe 105mm self propelled howitzers in position at Kursk

German Federal Archives

Skirmishes along the front began on the night of 4 July, with the main attack commencing in the morning of the following day despite Soviet artillery bombardment attempting to disrupt the initial movements. Hoping to disrupt the assembly of German forces, the masses of guns and Katyusha rocket launchers rained an enormous wall of fire on the attackers. German batteries replied in kind, shielding the initial advances and laying smoke screens, as an attempt by the VVS to interdict the Luftwaffe before they could get airborne to support the offensive likewise resulted in little gains, although Soviet losses in aircraft and crews were significant.

German motorcycle troops in action

German Federal Archives

The German offensive began with infantry spearheads of comat engineers (Sturmpioniere) crossing the various streams along the front, proceeding to ease the slopes on the eastern banks before the panzers forded them and charged ahead. The strongest German front came in the southern end of the salient, with the 4th Panzer Army under Herman Hoth serving as the spearhead with its concentrated armor. In the north, General Model likewise struck with his 9th Army, using highly mobile infantry and assault guns supported by Luftwaffe close air support.

A Soviet Maxim machine gun position

The attacking Wehrmacht encountered an enourmous Soviet defensive system, consisting of trench lines long enough to stretch to Spain if dug in a straight line, alone with mutually supporting hardpoints filled with anti-tank guns and interspersed with fields of some 30,000 landmines. German engineers sent radio controlled tanks to detonate the mines and open paths for the panzers, although many still fell victim to both mines and the Red Army’s tanks. Massive anti-tank ditches further slowed the German assault.

A German Ferdinand tank destroyer

Later war photo, German Federal Archives

The panzer formations were led by the massive Tiger I, the iconic German heavy tanks, whose armor was sufficent to protect it from anything the Red Army could throw at it from the front, and whoose 88mm gun was capable of destroying any enemy tank on the field. The Soviet T34 could only destroy one from relativly close range and from the side. The primary drawbacks of the Tiger were its slow speed and poor mechanical reliability. Supporting these vehicles were the new Panzer V “Panther” medium tanks, which in turn were showing to be a better match to the T34 than the older Panzer III and Panzer IV. Also, entering the fray for the first time, the Ferdinand tank destroyer, built from the chassis of rejected Tiger prototypes, these behemoths were armed with an even more powerful 88mm gun, but were very slow. Their lack of anti-infantry defenses made them extremely vulnerable to Soviet infantry, and losses of this type were severe from the first day.

Waffen SS Panzergrenadiers advance with a Tiger

German Federal Archives

Despite their difficulty in breaching the lines, the Germans made good on what penetrations they did make, advancing under the cover of the Luftwaffe’s Stukas and the new HS129 tankbuster aircraft. In seventeen hours, the 2nd SS Panzer Corps had broken through the first line, encountering the Soviet 1st Tank Army. In the face of heavy casualties, Stalin authorized General Vatutin to switch to the defensive, with counterattacks taking heavy losses against the massed panzer formations.

Red Army soldiers man an anti-tank rifle

Russian International News Service

The Soviets fully switched to defensive operations on 6 July, and when the German assaults began they ran into the dug in Red Army tanks, encountering heavy losses as they took the village of Ponyri. Heavy fighting would bog down Model’s 9th Army in the area, and with similar situations occurring in the south, Operation Citadel was nearing the end of its strength by 10 July. General Model’s forces had failed to secure their objectives at Ponyri and Olkhovatka, despite vicious combat in the former. Meanwhile, in the south, the Soviets were moving vast reinforcements to counter the advancing forces of General Hoth. His men had broken the first two Soviet lines, but a combination of dug in positions and effective support from the VVS had stalled their advance as well.

A JU87G Stuka with the new underwing mounted cannon pods

German Federal Archives

By this point, the Panzers were nearly depleted. Of 200 of the new Panzer V “Panther” tanks, less than two dozen remained operational by 11 July, and casualties had been heavy for other vehicles as well. As the Germans slowed, the Red Army was bringing up reinforcements, and it was becoming apparent that a massive armored clash was set to occur around the village of Prokhorovka, where three Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Divisions were positioned.

Soviet infantry and tanks advance

Russian Ministry of Defense

At dawn on 12 July, the Soviet 5th Guards Tank Army launched their counteroffensive at Prokhorovka, with over 600 tanks assaulting the German positions. Despite being outnumbered by a ratio of three to one, the Soviets were forced to attack in narrow fronts, resulting in very high casualties, with more than half of their tanks destroyed by the end of the day. The Soviet tanks charged into the German lines, finding the exhausted SS infantry unable to respond, as Red Army paratroopers jumped down from the T34s that had carried them into the battle.

A German SDKFZ251 halftrack during the fighting around Kursk

German Federal Archives

The Soviets began to overrun the SS positions, but were held up by a unit of Tiger tanks that managed to slow them in the afternoon, and as some units were overrun the fanatical SS men even resorted to ramming the Soviet tanks with their halftracks. Both the VVS and the Luftwaffe were active over the battlefield, with Sturmoviks and Stukas flying near constant sorties against the massed tanks on the ground, and even though the Germans still held the ground at the end of the day their position was now untenable. The commander of the II SS Panzerkorps, Obergruppenfuhrer Paul Hausser, was forced to order a withdrawal.

The withdrawal of the II SS Panzerkorps from Prokhorovka resulted in a decisive shift of the initative. The Red Army launched a concentrated counteroffensive. In the north, Operation Kutuzov saw the Soviets slamming into Model’s lines around Ponyri, as well as the rear of the salient he occupied, hoping to envelop them around Orel. The Germans were able to withdraw before this occurred, but were driven back to Rzhev by 18 August.

Red Army tanks enter Orel

In the south, the Soviets launched their attacks on 3 August, after resting and refitting their forces. This attack, designated Operation Rumyantsev, was directed toward Belgorod and Kharkov. Belgorod was liberated on 5 August, and a week later the Red Army was at the gates of Kharkov. The Germans were able to regroup and counterattack and halt the advance, but the Soviets were able to sever the main rail links between the city and the German rear on 22 August.

Soviet soldiers ride a lend-leased British Churchill tank past a wrecked German armored car near Kharkov

Despite the pleas of the commander of the German forces in Kharkov, General Werner Kempf, to request permission from OKW to withdraw, but the Fuhrer was adamant: Kharkov would be held. At the same time, Stalin ordered the capture of the city without delay, and as the Germans ammunition ran out von Manstein authorized the withdrawal on his own authority. By the morning of 23 August the Red Banner was again flying over Kharkov, and the remnants of the German force was in retreat to the River Don. The German attempt to regain the initative in the East had failed, and now the Red Army prepared to begin their long march westward toward Germany.

Commanders

Strength

The Battlefield

US Army