Operation Husky

Chapter 25

“His Majesty the King and Emperor has accepted the resignation from office of the Head of Government, Prime Minister, and Secretary of State His Excellency il Cavaliere Benito Mussolini”

9 July - 18 September, 1943

A British soldier reads a pamphlet on Sicily before departing North Africa for the next campaign

Even as the titanic battle for Kursk was beginning on the Eastern Front, the Western Allies were not merely standing by in the wake of their victory in North Africa. As far back as the conference at Casablanca in January Roosevelt and Churchill had, along with their respective commanders, been planning to cross the Mediterranean and invade Sicily, hoping to force the Germans to redeploy their forces as well as force Italy out of the war.

This had been a point of some contention within the upper echelons of the Allied leadership. While Churchill and the British were in favor of the planned operations against Italy, intending to open the Second Front in the south by targeting the weaker Axis partner, the Americans were instead in favor of moving directly to an invasion of Northern France via the Channel, beleving that to be the fasted route to destroying Germany herself and ending the war. In the end, however, the British won out, and Operation Husky was born.

An American Waco Glider after landing Sicily

It had, by this point, been not quite two months since the final destruction of ther Italo-German forces in Tunisia, but the Anglo-American forces there had been building their fleet since the landings in Vichy Algeria in January. The assembled fleet, along with the ever growing army on the ground and air forces to cover them, had also been moving against several islands in the Mediterranean, clearing the path for eventual invasion with a massed force of two field armies, one American and one British. The US 7th Army was under the command of the famously hard-charging General George S. Patton, while the British 8th Army remained under the command of the celebrated hero of El Alamein, Bernard Montgomery. Overall command would remain in the hands of the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

US soldiers aboard a transport bound for Sicily

On the other side, the defenders were in a fairly shoddy state. The Regio Esercito had been badly worn down by the years of fighting in Africa and a disastrous outing on the Eastern Front around Stalingrad over the previous winter. The Germans had troops stationed in Italy and Sicily as well, but with newly opened offensive at Kursk their strength in the region was relatively low. The Italian 6th Army mustered some 600,000 troops for the defense, along with an additional 30,000 Germans. The Germans were in two divisions, including the Luftwaffe’s powerful Herman Goring Panzer Division. Their modern Panzer III and Panzer IV tanks represented the best armor available on the island, with most Italian units equipped with a smattering of older light tanks.

An American cargo ship bringing in ammunition to Sicily explodes after being hit by a German air attack

The Allied fleet set out for Sicily in the evening of 9 July, 1943, encountering a nasty belt of storms as they made the 90 mile crossing to the island. In the air things were not much better, as the airborne vanguard of the assault ran into its own difficulties. Gliders carrying British paratroopers were released off target by inexperienced pilots, with most landing in the pitching seas and the rest scattered across the operational area. Only 12 of the 144 actually landed in their intended target zones. These landings began at 2330 hours, along with US paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division, who jumped from their C47 transports and were scattered across a huge area just as their British counterparts had been. Badly disorganized, the paratroopers adapted as well as they could, attempting to secure their objectives and causing disruption behind the intended beachheads.

British troops and vehicles land on the Sicilian coast

Aerial counterattacks were scattered, as both the USAAF and the RAF had been pounding the bases of the Luftwaffe and the Regia Aeronautica over the preceding weeks, with only two operational airbases in the area and the local Axis air forces reduced to less than 50% of their operational strength.

A British soldier surveys a devastated Regia Aeronautica base in Sicily

The relatively lackluster defenses of Siciliy could also trace their origins to an elaborate and effective British deception operation. Codenamed Operation Mincemeat, this had involved taking the corpse of a homeless man who had died after accidentally consuming rat poison and creating an entire false identity, complete with records and even photos of a secretary posing as a girlfriend. The body was then taken via submarine to the Spanish coast and dumped into the sea, to be found by Franco’s Spanish authorities. As anticipated by the British, they quickly handed over the secret documents on the body to their German friends, detailing a planned invasion of Greece. The deception made its way all the way to Hitler himself, who ordered German units transferred to the Balkans despite the pleas of Mussolini to shore up the defenses of the Italian homeland. In addition, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the famed “Desert Fox”, was sent to take command in the Balkans.

The corpse of Welsh vagrant Glyndwr Michael, about to be loaded onto a submarine to take his part in Operation Mincemeat

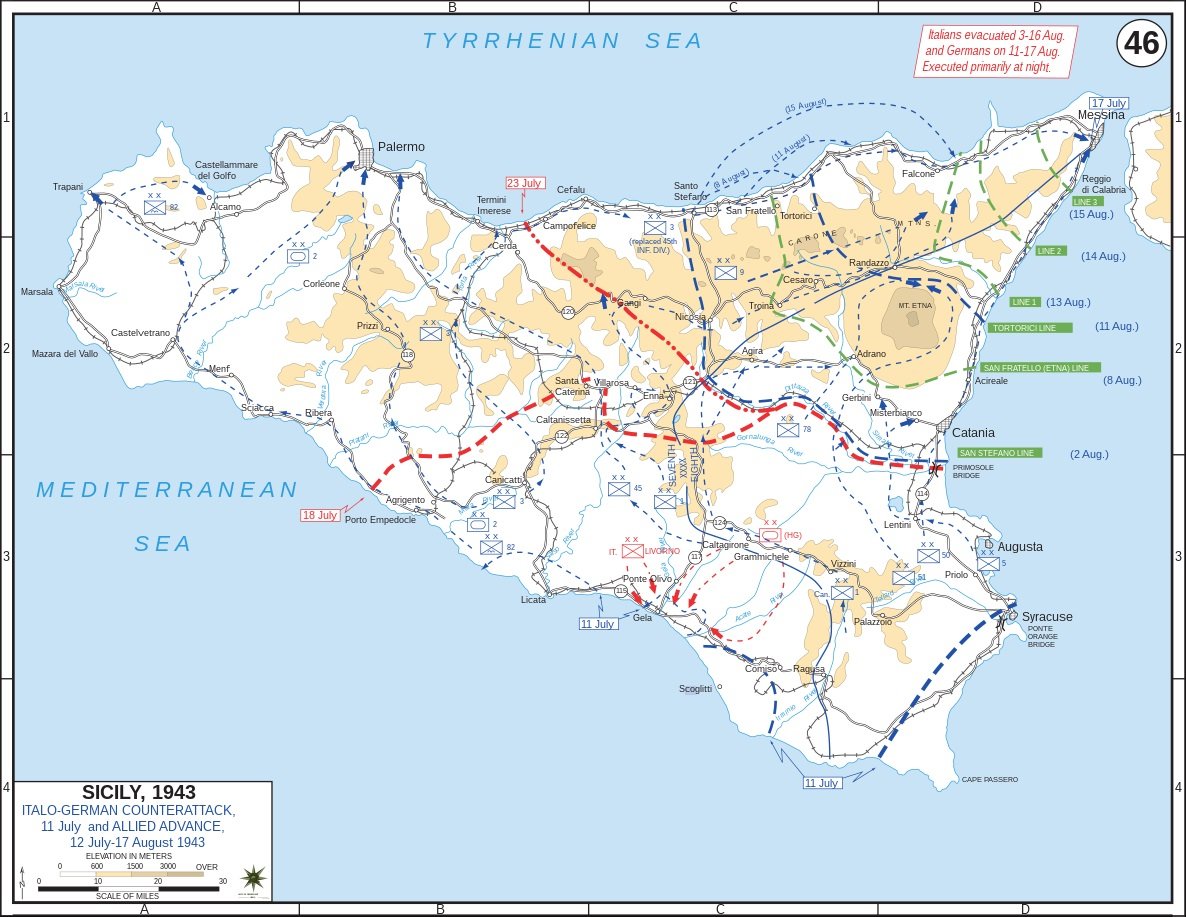

The amphibious landings on the morning of 10 July were met with limited hesitance, despite orders being issued by the headquarters of the Italian 6th Army after midnight to go to full alert. Montgomery’s forces encountered little resistance as they landed and secured the critical seaport of Syracuse, while Patton’s forces were able to move in quickly Italian counterattacks around Gela. A subsequent counterattack was made inland by the Herman Goring Panzer Division at Piano Lupo, but this too was repulsed by the Americans with the aid of offshore naval gunfire.

Americans going ashore at Gela

In the wake of these attacks, Patton elected to reinforce his positions around Gela with an airborne drop on the night of the 11th, and this would turn into a disaster, as overeager anti-aircraft gunners shot down numerous transports, causing the paratroopers 10% casualties from friendly fire before even jumping. Despite this, progress was steady in both the American and British sectors over the coming days.

A knocked out German Tiger tank on a Sicilian street

German reinforcements were on the way, however, with elite German Fallschirmjager units being rapidly redeployed from France. Their arrival served to stall the British advance, prompting Montgomery to press for and receive permission to flank around them at Catania. This move allowed the 8th Army to outflank the Germans, but also served to incense Patton, whose 7th Army was now to be relegated to guarding Monty’s flank from the relatively weak Italo-German forces in western Sicily.

Smiling Italian soldiers wave white flags as they reach American positions to surrender

Not content to do so, Patton launched a “reconnaissance” mission toward Agrigento on 15 July, aiming to open the door to the Sicilian capitol of Palermo. This did just that, and Patton’s men were in the city by 24 July.

The Fall of Palermo, along with the disasterous direction of the campaign in Sicily in general was having a profound ripple effect throughout all of Italy. This was merely the most recent of what was perceived as a long string of failures and defeats that were generally viewed as being the fault of the Duce and the National Fascist Party. By mid May King Victor Emmanuelle III, who had long been a backer of the Duce, was beginning to have doubts, and his support among the populace was not helped by a rambling, incoherent speech in late June.

Canadian troops enter Modica

With the campaign in Sicily proceeding as it was, there was an attempt to convene the Italian Senate, although this was blocked by Mussolini. This left the Grand Council of Fascism as the only legislative body that could meet to face the crisis, which the Duce authorized to take place on 24 July, following a meeting with Hitler and the OKW. That meeting went poorly, with the Fuhrer excoriating the faltering Duce on his inaction, and angered when Mussolini left to return to Rome earlier than expected.

The Palazzo Venezia, Mussolini’s official residence and the seat of the Grand Council of Fascism

The Grand Council convened in the late afternoon of 24 July, with the palace notably devoid of Mussolini’s bodyguards, but with armed Blackshirts on the grounds. After some deliberation, the first vote in the twenty year history of the Grand Council was put forward, to decide between an order for the elimination of the last elements of the state and armed forces not under the control of the Party, and an abdication of the Party’s role in such matters in favor of the King. The latter order, proposed by fascist minister Dino Grandi, was passed, effectively removing the Duce and from power and ending the Fascist Party’s control over the Kingdom of Italy.

King Victor Emmanualle III at a function earlier in the war

Mussolini requested and was granted an audience with King Victor Emmanuelle III the next day, where he presented the order from the Grand Council and attempted to convince the monarch that it was not required to remove him from office. This was to no avail, as the King was now convinced that the Duce needed to go, and he informed Mussolini that he had already instructed Marshal Pietro Badoglio to form a new government. Dejected, Mussolini was taken into custody by the Carabinieri, who transported him via ambulance to his prison, which eventually ended up being the a ski resort atop the Campo Imperatore to the northeast of Rome. Concurrently, the MSVN (Blackshirts) found their headquarters surrounded by Army troops, and they surrendered without resistance. With these actions, the two decades long Fascist rule of Italy came to an end, leaving the county to face an uncertain future as the Allied invasion continued and their erstwhile German Allies prepared their response.

Marshal Pietro Badoglio, new Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Italy

In Sicily, the Anglo-American advance continued despite the best efforts of the Regio Esercito and the Wehrmacht. The British 8th Army was stalled its advance on Messina, and the US 7th Army was thus ordered to swing eastward to aid them in their assault. Ringed by mountainous terrain and in the shadow to the volcanic Mt. Etna, the city posed a significant obstacle to the attackers, especially in light of the defensive positions erected by the Germans in a line from the eastern coast to the northern coast, with Mt. Etna as a centerpoint.

A column of Italian POWs are marched away by American soldiers

By this point, the Regio Esercito was in a state of collapse, and the Germans were essentially in full control of the campaign. OKW had already decided the the island was lost, and the plan was now to withdraw behind the Etna Line and begin to evacuate to the mainland via Messina, despite the intentions of the Italian leadership to fight to the end in Sicily.

Patton and the US forces were, by now, convinced that the British leadership thought little of them and their abilities, and were thus determined to reach the prize of Messina before Montgomery and the British. Assigned the northern route to attack the city, the Americans began a drive along Highway 113, which posed the most direct route, with the 1st Infantry Division moving up along Highway 120. By 31 July the British were advancing on Centuripe, which would in turn open the door to Adrano, a key point in the Etna Line. The Americans on that day also entered Troina, which was an important node in the northern sector of the line.

Patton on the road to Messina

Patton had intended to replace the weary 1st Infantry Division with the 9th Infantry Division after the fall of Troina, but the defenders proved particularly strong at this anchor of the Etna Line. With a German Panzergrenadier division and elements of an Italian infantry division dug in around the town, the battle of Troina would last a week, as the Americans fought to root out the well dug in defenders from the town and the numerous emplacements overlooking it. As this battle went on, with both sides launching numerous attacks and counterattacks, a similar fight was ongoing along the northern coast at San Fratello, as the US 3rd Infantry Division engaged the terminus of the Etna Line. An amphibious landing was launched to outflank the town on the night of 7 August, which achieved complete suprise upon an enemy that was already retiring further eastward.

British soldiers clear buildings during urban fighting along the Etna Line

The British, for their part, had captured Catania on 5 August, and Adrano itself had fallen the next day. On 13 August Randazzo was taken, leaving Monty’s men on the slopes of Etna itself, and the Etna Line was effectively broken. The Germans had begun their final stages of evacuation on 11 August, and Patton’s 3rd Army entered Messina without major resistance on 17 August, beating the British forces into the city. With that, the Allied conquest of Sicily was complete, and all eyes turned to the Italian mainland.

Patton shakes hands with Monty in Sicily

Meanwhile, the fallout from the deposition of Mussolini and the Fascists was still ongoing. Badoglio’s government had officially announced that it planned to continue the war, but Hitler was dubious of this conviction. Significant German forces had been entering Italy since 26 July, and rumblings from Rome about surrender continued, as the Italian Armed Forces made their preparations for a defense of the homeland even as the military collapsed. Regardless of the future, it was clear at this point that the Fall of Fascism also meant the end of Italy as a major power in the war, and the new government in Rome was left with the daunting task of maintaining even a semblance of sovereignty as their partnership with Germany theatened to give way to subjugation.

Commanders

Strength

The Battlefield

US Army