Spring, 1944

Chapter 31

The Fall of Rome

April - June

Europe: The Eastern Front

At the beginning of April of 1944 the War in the East was ready to enter a new phase, as the Red Army moved to enter Axis home territory for the first time. The Soviet 2nd Ukrainian Front had been driving across the Ukrainian SSR since the beginning of the year, and by now were positioned along the Romanian border, with an isolated area around Odessa remaining under their control as well as the Crimea.

A column of German Panther tanks advance in Romania

German Federal Archives

On 9 April, 1944 the Red Army crossed the frontier and entered Romania, posing a direct threat to the only major oil producing region in the German sphere of influence. Driving first on Targu Frumos, the Soviets captured the town from defending Romanian troops, but were soon met by the elite German Grossdeutschland Division, which mounted a strong counterattack supported by additional Romanian divisions. This was successful, and the Red Army was forced to withdraw. A second offensive was made toward Targu Frumos in early May, but this too was blunted by reinforced Axis units, and with that the country was, for the moment, secure, as the Soviets turned their attentions elsewhere.

Soviet tanks advance on Odessa

Russian Army

Meanwhile, the Soviets were squeezing the Germans trapped in Odessa. The exhausted German 6th Army (reformed after its destruction in Stalingrad over a year prior) had been further gutted by sending its units into Romania to blunt the Soviet invasion there, and had little left to prevent the Red Army from crossing the Bug River at the start of April. Soviet forces advanced against the retreating Germans with the intent of enveloping the 6th Army in Odessa, and an attempted counterattack was blunted on 7 April, with many German formations disintegrating and retreating in panic.

Soviet troops march through Odessa after the city’s liberation

On 10 April Odessa was liberated by Soviet forces, with the remnants of the German 6th Army breaking out toward Romania under heavy attack by both partisans and the Red Air Force. They attempted to dig in along the Dniester, although Soviet units were able to secure bridgeheads before this was fully accomplished.

Soviet soldiers examine German armor abandoned in Podolsky

Farther to the north, the Red Army had enveloped the German 1st Panzer Army at Podolsky near the Soviet-Romanian border at the end of March, in the process splitting the two main forces of the German Army Group South with a wedge created by the 1st Ukrainian Front. Almost 200,000 German troops were trapped in the new pocket, with their remaining panzers desperately low on fuel. With little choice, the Germans launched a breakout attack westward, hoping to link up with the SS forces holding the fortress city of Tarnopol. This was accomplished by 6 April, with the battered remnants of the 1st Panzer Army reaching friendly lines, albeit with most of their tanks and heavy equipment abandoned in the heavy spring mud.

A Red Army machine gun post along the Crimean coast

Russian International News Service

To the east, the Soviets launched yet another offensive on 8 April. Despite the Soviets having isolated the Crimean Peninsula in late 1943 the defending German and Romanian forces were still holding out, with supplies coming in via the Black Sea. When the Soviet offensive finally came it swiftly overran the German positions near Kerch on the eastern end of the Crimea, driving the defenders back toward the port of Sevastopol, site of the stiff Soviet defense in 1942. Despite this, the damage done to the city’s defenses by the attacking Germans served to prevent them from doing the same, and a large scale naval evacuation was ordered in late April.

A Soviet T34 tank enters Sevastopol flying the colors of the Red Navy

The evacuation found itself under heavy attack by Soviet bombers, with only limited interception by the Luftwaffe or Romanian fighters. In addition, as the Red Army gained ground in and around Sevastopol shore batteries became increasingly problematic, as did ships of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet. On 9 May Sevastopol was liberated by Soviet troops, and the last frantic evacuations via small ships and landing craft was terminated on 12 May. With the Crimea and Odessa back in Soviet hands, the Red Navy was again in a dominant position in the Black Sea, and the VVS was in a position to launch bombers against the Romanian oil fields so critical to the German war effort.

Finnish soldiers in a trench await a Soviet attack near Vyborg

Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture

The end of the Siege of Leningrad had not been the end of the war in the north either, with the Soviets launching a large scape offensive operation against Finland in June of 1944. The Finnish front line was overrun on the first day of the offensive, and the second line was breached only five days later. Ten days after the start of the offensive the Soviets had taken the city of Vyborg, with the Finns again withdrawing to another line extending from the Baltic coast at Viipuri to the shore of Lake Ladoga.

One of the new Soviet IS-2 heavy tanks during the advance into Finland

As the situation deteriorated in mid June, Finnish leader Gustaf von Mannerheim requested reinforcement from the Germans, receiving additional supplies of infantry anti-tank weapons along with a Luftwaffe detachment and ground troops. Despite all of this, the Soviet offensives continued to slam against the Finnish lines, and at the end of June Finland opened negotiations with the Soviets to surrender.

Europe: Italy

The ruins of the Monte Cassino Monastery

British Army

In the mountains of Italy, the Allies remained locked in battle for the monastery at Monte Cassino, with the Germans stubbornly refusing to yield the ruined abbey as they had for months. With plans by now well underway for an Allied invasion of France across the English Channel, it was considered imperative that the pressure be maintained on the Germans in Italy to ensure that as many units as possible were tied down there before the re-opening of the Western Front.

Preparations for the next major strike at Monte Cassino took the entireity of April and it was only on 11 May that the attack was launched, with thirteen Allied divisions of US, British, French, Canadian, Indian, New Zealander, South African and Polish troops attacking the Gustav Line. Successful bridging by Allied engineers allowed for the withstanding of the German panzer forces that had smashed previous assaults, and the Germans began to be pushed back. After vicious hand to hand fighting the German defenders of the monastery were pushed out by the Polish II Corps, who raised their colors of the rubble of the abbey on 18 May.

Polish soldiers move through the ruins atop Monte Cassino

In the wake of the fall of Monte Cassino, the Germans withdrew to the Hitler Line, but this only held until 25 May, when British forces broke it and forced the Germans to withdraw farther north. Two days prior the Allies had launched an offensive from the beachhead at Anzio, slamming into the German’s flank behind the Hitler Line and causing pandemonium as the Germans attempted to reorganize their lines.

A wrecked US Sherman tank near Cisterna

US National Archives

After heavy house to house fighting the town of Cisterna fell to the US 3rd Infantry Division on 25 May, with the German 362nd Infantry Division being almost totally destroyed in the process. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German theater commander in Italy, committed what panzer forces he had in an effort to stall the Allied drive and hold the main routes north open as he began to move for the Caesar Line just south of Rome. This move was abetted by the Americans’ decision to pivot their forces breaking out of Anzio directly northward, allowing Kesselring’s troops to escape as they closed on the Italian capitol.

US armored units enter the city of Rome

US Army

The Caesar Line was breached on 30 May, with the Americans exploiting a gap in the German positions that forced the abandonment of the entire line. On 2 June Kesselring received orders directly from Hitler to abandon Rome rather than turn it into another Stalingrad, and he complied. As a result no resistance was offered as US troops marched into the Eternal City two days later.

American tanks pass the Collesium and cheering crowds as Rome is liberated

US Army

Following the Fall of Rome the Germans continued their retreat northward, setting up at the Trasimene Line, which would hold to the end of the month of June, as the Germans prepared to pull back to their last major line in Italy, the Gothic Line along the northern Appennine Mountains.

Europe: The Air War

Buildings burn in Berlin during an RAF raid

German Federal Archives

As the air war continued its inexorable escalation, the Axis powers found themselves being hammered by the combined Allied air forces. Logistical systems suffered from instances of paralysis, while factories had to be repaired or relocated to allow for the production required for what was by now a war of attrition.

A USAAF B17 is damaged by friendly bombs dropping on Berlin

US Army

The Fuhrer’s birthday on 20 April was met with celebrations in Germany along with a record setting Allied air raid on the German capitol, and raids on the vital oil infrastructure in Romania witnessed continually escalating attacks even as the Red Army neared them on the ground. Incursions were now being made into neutral Swiss airspace as well by incoming bombers. Accidents took place as Switzerland was bombed by mistaken Allied fliers, while at other times their airspace was used to sneak bomber flights into German airspace.

A German HE177 heavy bomber of the type used for Steinbock

German Federal Archives

In the skies over Britain the Luftwaffe had been present in large numbers since the start of the year, with Operation Steinbock becoming known as the “Baby Blitz” by those on the ground. Despite this attempt at resuming their own bombing campaign against British cities, the Luftwaffe had suffered severe losses, and by the time the operation was cancelled on 29 May the losses sustained by Luftwaffe bomber squadrons was so severe that the Luftwaffe’s ground attack force was essentially destroyed in the west, just in time for the anticipated invasion of the continent. With losses of over 70% of their bombing forces, the Luftwaffe would never again be able to menace Britain with fixed wing aircraft in quantity.

A German V-1 Buzz Bomb is pushed to a launcher by a ground crew

German Federal Archives

While the Luftwaffe’s bomber forces had been decimated by Steinbock’s failure, the Germans new “Vengeance Weapons” (Vergeltungswaffen) were just becoming operational in mid-1944. The Fieseler V-1 was a cruise missile powered by a pulsejet engine and designed to be fired from a ramp-type launcher against targets in Britain. The first such weapons wer launched in mid June of 1944, although their lack off accuracy ensured that they had a relatively low number of actual target hits versus random strikes on civilian areas.

Europe: The War at Sea

Tirpitz camouflaged in Norway

US Navy

At sea, the Kriegsmarine had by this point in the war lost most of its surface fleet, and most of what remained was confined to bases in the hope that they would not be destroyed by the vastly superior Allied naval and air forces. The infamous Bismarck had been sunk in battle three years ago at this point, but its sister, the Tirpitz, remained operational but confined to a Norwegian fjord. Attacks had been made in the past by the Royal Navy, and on 3 April a carrier group was sent to strike at the German behemoth once again.

An armorer scrawls a message on a bomb meant for Tirpitz aboard the carrier HMS Furious

Royal Navy

Surprising the Germans, the Fleet Air Arm descended on the German battleship with forty dive bombers, with several strikes on the battleship as its flak gunners scrambled to their stations. Several bombs struck the battleship, inflicting heavy damage across two waves with limited casualties for the British. Subsequent attacks were launched in late April, although these had no such success, and by mid June the Tirpitz was fully operational once again.

The Tirpitz is hit by bombs dropped by Fleet Air Arm planes

Royal Navy

Later in April, with plans well underway for the planned invasion of the continent, the Allies in Britain were staging large scale training operations for amphibious assaults. On 22 April Exercise Tiger was commenced, with 30,000 Allied troops slated to storm the beaches of Slapton Sands for a live fire practice landing. Plans were for these exercises to be as realistic as possible, with a live fire naval bombardment to accompany the landings. Unfortunately, due to a communications failure, these shells landed on the prematurely landed first wave, inflicting serious casualties.

A German E-Boat operating off Norway

US Navy

On the next day (28 April), another disaster struck as a convoy of landing ships bound for Slapton sands laden with armored vehicles and specially trained assault engineers was set upon by a flotilla of German E-Boats operating out of Cherbourg. The small German craft sank two landing ships and damaged two more, killing almost eight hundred men and wounding hundreds more. The Germans took no losses in the engagement as the Royal Navy destroyer escort had been in the process of replacing ships at the time of the attack.

Europe: Under Occupation

Despite their setbacks, the Germans still held control of most of the continent. In France, additional units were being redeployed in anticipation of the Allies re-opening the Western Front. Resistance activity was likewise escalating, despite the harshness of German reprisals, which included massacres of entire villages worth of civilians at the hands of the SS.

SS police round up Jews in Budapest

German Federal Archives

In Hungary the Germans had begun an outright occupation of their erstwhile ally, and the SS now had free reign to move against the country’s Jewish population. Mass deportations began, with thousands forced onto cattle trains and sent northward to the feared concentration camp at Auschwitz in Poland. By the end of June the number of Jewish Hungarians handed over the the Nazis had crossed the 400,000 mark, under the command of the infamous SS Obersturmbannfuhrer Adolf Eichmann.

A Polish resistance fighter armed with a WZ28 automatic rifle

Polish National Archives

In the east, where the Germans' hold was looking increasingly tenuous as the Soviet armies advanced, the Polish resistance was becoming increasingly active. Open battles were waged in areas such as Osuchy, where the German occupation forces managed to bring a contingent of the Polish Home Army to battle in late June, destroying a force of over 1,000 insurgents. Despite this, the Poles were still organizing for something much larger: reforming the destroyed Polish Army underground, in anticipation of liberating their homeland before they could exchange German occupiers for Soviet ones.

Pacific: Southern Islands

American landing craft head for Hollandia, New Guinea, as the cruiser USS Boise shells the beaches

US Navy

As the battle for New guinea continued unabated the Allies launched a new phase of the campaign with landings in the northwestern portions of the island, with landings at Hollandia and Aitape on the northern coast of the islands, behind the Japanese lines. Amphibious assaults by US Army units commenced in late April, with the Japanese defenders being overrun fairly quickly due to the achievement of surprise by the attacking forces, with the Japanese pushed back into the interior of the island.

American soldiers march through the jungles near Hollandia

US Army

Meanwhile, Australian troops completed the capture of the Finnesterre Range in late April, along with the old German colonial capitol of Madang, leaving them in control of the Huon Peninsula. The Japanese in turn withdrew toward the small island Wakde on the coast, but this position was also under grave threat after the American landings farther west along the northern coast. US troops landed on the small island on 17 May, and four days later it had been secured.

An Australian position on Shaggy Ridge in New Guinea

American M4 Shermans come ashore at Wakde

US Army

In subsequent moves, the Allies moved to push the Japanese farther west, with heavy fighting taking place as several important objectives are taken and held by American and Australian forces. As the battle continued for the mainland of New Guinea, Allied leaders, in particular General Douglas MacArthur, were now looking toward the next phase of the war in the Pacific. To this end, it was decided that the island of Biak, located just to the northwest of New Guinea must be taken as a prime base for MacArthur’s planned invasion of the Philippines.

US forces land at Biak

US Army

As US forces began to land on Biak on 27 May it became apparent that American intelligence had grossly underestimated the strength of the defending Japanese garrison. Despite the ease in overcoming a small attack by Japanese tanks on the beaches the bulk of the defenders had pulled back inland to ambush in the invasion forces, inflicting heavy casualties.

A Japanese Ha-Go tank at Biak

US Army

As the month of June wore on, heavy fighting raged on Biak, with the Japanese retreating into cave systems to harass the Americans and prevent them from building up airbases on the island. The Japanese intended to further reinforce their garrison on the island, and tasked significant naval and air assets to it, but developments elsewhere forced these units to be sent elsewhere before their arrival, and the Japanese defenders on Biak were doomed to holding out until destroyed as June came to an end.

Pacific: Southeast Asia

Indian troops advance with a Lee tank on Japanese positions near Imphal

British Army

The month of April opened in Burma with the Indian XXXIII Corps partially enveloped at Jotsama, but this was soon relieved as the British Indian Army launched a new offensive toward Burma with the intention of eliminated the Japanese toehold in India. This was the result of a Japanese attempt to enter the largest British colonial possession in order to ferment revolution there as well as to cut off Allied supply to China, with the attack launched on 6 March. Despite this, their attacks had been halted as a result of a heroic stand around the residence of the Deputy District Commissioner for Nagaland, and its tennis court would give name to the ensuing battle.

The Japanese reached the Commissioner’s Regiment on 8 April, and began to assault the position against a defending force, taking the building after a brief battle with bayonets and knives. The defenders retreated just uip the hill to the attached tennis court, where British reinforcements arrived. Subsequent Japanese attacks over the next few days occured multiple times per hour, but the British and Indian defenders could not be dislodged. In one notable incident a British machine gunner was able to survive a bayonet attack and turn his weapon on his attacker, killing him with a barrage of .303 bullets. Japanese attacks continued unabated for almost ten days, with heavy artillery backing the attackers as the British and Indian troops held firm. The arrival of additional troops as well as tanks broke the Japanese on 17 April, with the stand at the Tennis Court being compared to Thermopylae in later accounts.

An RAF Hurricane strikes Japanese positions in Burma

Royal Air Force

Despite the siege being lifted, the area of the Tennis Court remained a scene of brutal combat until mid May, with the Japanese continuing to press their attacks, finally capturing the Tennis Court on 10 May, although they were subsequently pushed back out permanently on 13 May. This action was a component of a larger general offensive in the Kohima area, backed by numerous newly arrived artillery batteries and RAF attack squadrons, making use of the older Hawker Hurricane fighters to great effect. As the Japanese retreated, they were able to take prepared defensive positions and slow the attack, as the jungle mud slowed and stopped British tanks supporting the advance. Despite this, Japanese supplies and reserves were depleted, forcing them to withdraw in late June.

A 75mm pack howitzer in action at Myitkyina

Elsewhere, the Chinese were launching their own attack into Burma. Hoping to capture the strategically important Japanese air base at Myitkyina, the Chinese Expeditionary Force attacked in late May, having recently been reequipped by the Americans. Joined by the American 5307th Composite Unit (the famed Merrill’s Marauders), they captured the base on 17 May, followed by a siege of the Japanese garrison in the adjoining town, reinforced by troops flown into the intact airfield. The siege was ongoing as June came to an end, with attempts to divert the British Chindits to reinforce them being prevented by the exhausted state of these forces after their own month-long battle to capture Mogaung.

Chindit leader Brigadier “Mad” Mike Calvert issues orders to his men at Mogaung

Imperial War Museum

The Battle of Mogaung had consumed the entirety of the month of June for the Chindits and their Chinese reinforcements. The Chindit operation had been launched with the intention of taking some of the pressure off the defenders in India, but under the command of the cantankerous and Anglophobic American General Joseph Stillwell, the British special operations force was sent into battle as line infantry, incurring enormous losses. When the Union Jack was raised over the town (the first in Burma to be liberated in the war), Stillwell’s headquarters repoted to the BBC that the Chinese had taken the town, resulting in a famous quip from Calvert to his American superior: “Chinese reported taking Mogaung. My Brigade now taking umbrage”.

Pacific: China

Street fighting at Changsha

In mid April the Japanese launched another offensive, this time into central China. Designated Operation Ichi-Go, this plan was essentially a contingency for the loss of the Pacific Island Campaign in order to secure the Empire’s position in mainland Asia and secure overland routes for supply from Southeast Asia to Manchuria and Japan itself. The other primary objective was the neutralization of US bomber bases in China, which directly threatened the Home Islands. In turn, even as the war turned decisively in favor of the Allies the government and Army of Chiang Kai-shek’s China was beginning to totter under the weight of the economic devastation of almost a decade of war in their homeland, and in addition much of the Chinese Army was deployed to aid the Allies in Burma.

The Japanese struck on 17 April, driving on the city of Changsha in the Province of Henan with 700,000 troops, outnumbering the Chinese defenders by a factor of ten to one. The disorganzied ROC forces quickly collapsed, leading to the rail connections to Changsha being cut by early May and the destruction of the bulk of the Kuomintang’s armies in northern China. Subsequently the cities of Hengyang and the Provincial Capitol of Changsha fell to the Japanese. This would have grave reprocussions for the Republic of China, as General Stillwell leveraged the disaster to blame Chiang and as a result a serious rift developed over the threat of cutting US war aid. In the end Chiang was victorious, with Stillwell being recalled some months later.

The Pacific: The War at Sea

A Japanese merchantman sinks, as viewed from an American periscope

US Navy

Across the vast swath of the Pacific, American submarines were achieving sucess that even the vaunted U-boat crews of the Kriegsmarine could only dream of. Losses of Japanese merchantmen and warships continued to drastically escalate, with the early war issues with American torpedoes having been corrected to deadly effect. Convoys attempting to supply and reinforce the various island garrisons of the Japanese Empire encountered serious losses en-route, and the warship losses were something that the increasingly depleted Imperial fleet could scarcely afford.

The carrier USS Bunker Hill narrowly avoids being hit by a Japanese bomb in the Philippine Sea. A Japanese plane can be seen overhead, its tail shot away.

US Navy

19 June would see the next major naval battle of the Pacific War, as US and Japanese fleets clashed in the Philippine Sea. Attempting to respond to American attacks on the Marianas, the Japanese moved to hit the attackers with everything they could bring to bear, as the capture of the islands would allow US bombers to strike the Home Islands regardless of positive developments in China. This was intended as the cumulation of the IJN’s decisive battle doctrine, with almost the entire surviving Japanese fleet committed alongside land based aircraft in an all out attack to cripple the Americans and turn the tide of the war. Heading this force was the new carrier Taiho, a new, armored design intended to address the weaknesses of earlier Japanese designs.

The Japanese carrier Zuikaku maneuvers to avoid attacking American aircraft

US Navy

Detecting the Japanese force as it departed the Philippines, US submarines reported the movement and in response US carriers were dispatched to intercept them. The initial Japanese attack came from fighters based on Guam, which were destroyed with almost no losses by the American carrier fighters. Subsequent Japanese carrier formations took time to form up, allowing the Americans to intercept them before the carriers could be hit. The Americans responded in kind, with a submarine sinking the new carrier Taiho with a single torpedo hit, while another sub hit the carrier Shokaku with a spread of torpedos and sank her as well.

It was not until the next day that the American carrier planes located and attacked the Japanese fleet. Hitting them with over two hundred planes, the carrier Hiyo was also sunk. The remaining Japanese carriers also incurred damage, and were forced to withdraw with three carriers lost and over five hundred planes shot down in what became known to the Americans as the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”. The decline in Japanese pilot quality due to losses early in the war was beginning to show, and the Philippine Sea would be the last major carrier battle of the war in the Pacific.

Pacific: Air War

Crews load an Avenger aboard the HMS Illustrious

Royal Navy

As the Turkey Shoot went on, elsewhere the air war in the Pacific was about to enter a new phase. By April most of the aircraft stationed at the major Japanese base on Truk had been destroyed, severely crippling the air defense of the central Pacific region. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy was moving carriers in to reinforce the US Navy, with planes from the HMS Illustrious striking the Japanese in Indonesia, joining US planes to strike bases and infrastructure.

New USAAF B29 bombers at a base in India

US Army

In addition, the US Army Air Force was introducing a new heavy bomber type into the theater. The Boeing B29 Superfortress had been designed as a “superbomber”; being a pressurized aircraft with a range of almost 5,000 miles with a full bomb load. The first combat operation of the B29 was made on 5 June, flying from bases in China to strike railyards in Bangkok, capitol of Japanese-allied Siam. The first raid on Japan took place ten days later, with B29s hitting the steelworks at Yawata in the first raid on Japan itself since the Doolittle Raid of 1942. This act heralded the start of the strategic bombing campaign on Japan, which, much like that on Germany, would continue until the end of the war.

Political Developments

A German JU290 in flight

US Army

On the front of politics, the internal situation within the Axis Alliance was deteriorating. With nations such as Hungary, Romania and Finland contemplating capitulation, the Germans were increasingly isolated, and even plans for long range cargo flights to Japan with the JU290 heavy transport were aborted due to arguments over Japanese concerns regarding the provocation of the Soviets. In Italy the Duce, still nominally head of the Italian Social Republic, was a broken man, attending high level conferences and being allowed as much input on the direction of the war as the wallpaper.

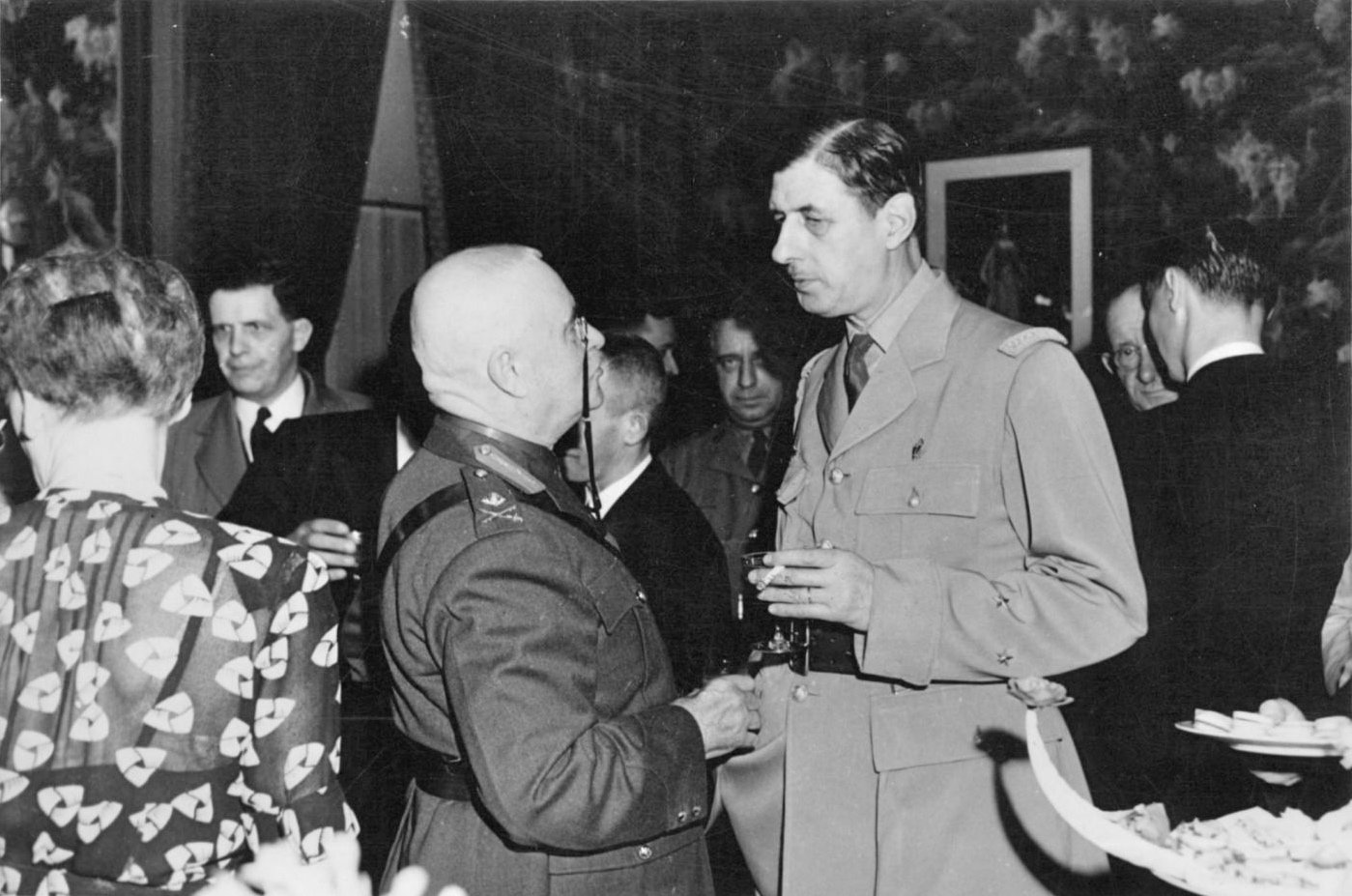

Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle at a conference in Canada

Canadian National Archives

Within the Allied camp, the British had released Mahatma Ghandi from prison in the face of the Japanese invasion of India, with the independence leader’s failing health giving concern that his death would inflame anti-British sentiment at this critical juncture. Meanwhile, in the United States President Roosevelt informed the ailing Filipino President Manuel Quezon that his country would be granted full independence after the end of the war.

In Italy the Badoglio government relocated to Rome after it was taken by the Americans, following a reorganization of the cabinet. Another nation was also preparing for a return to its homeland as well, as Charles de Gaulle’s Free France prepared for the impending invasion. Resistance movements were being consolidated as the Free French Forces of the Interior, while General de Gaulle himself consolidated his power over Free France with the declaration of the Provisional Government of the French Republic in anticipation of a resumption of civil control over metropolitan France.