Pietro Badoglio

“I have conquered an empire for Italy and Mussolini has thrown it away.”

On 28 September, 1871 Mario and Antonietta Badoglio of Grazzano Monferrato, a small commune in the northern region of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy were blessed with a son. This young man, whom they named Pietro, would be enrolled in the Royal Military Academy at Turin at the age of 17 in 1888. He received his commission in 1890 as a Second Lieutenant, and he remained in school for an additional two years, entering active service in 1892 as a First Lieutenant in the Artillery.

Italian artillerymen in Ethiopia during the war of 1895

Thus commissioned, he was promptly sent to Ethiopia, where the Kingdom of Italy was engaged in a war to conquer the African nation that they viewed as rightfully theirs during the ongoing scramble for the continent by the various European powers. taking part in the Battle of Adwa in early 1896, Badoglio would thus be a witness to the defeat that would lose his country the war, and upon returning home and to the academy, leaving it as a Captain in 1902.

Next for Badoglio and Italy came the Italo-Turkish War in 1911, with Badoglio being sent to fight in Libya against the aged and weakened Ottoman Empire. During this conflict Italy would emerge victorious, capturing the territory from the Turks. Badoglio, for his part, was decorated for valor and received another promotion during the conflict.

An Italian aircraft in Libya in 1913. The Italo-Turkish War for the province would see the first use of military aircraft in history

As the world erupted into conflict in 1914 Italy initially remained on the sidelines, citing the defensive nature of their membership in the Triple Alliance. In May of 1915, following secret negotiations with the Entente, the country entered the war on their side, turning on their earstwhile Austro-Hungarian allies. Badoglio was by now a Lieutenant Colonel, serving as a staff officer in the Italian 2nd Army. In this capacity he commanded the 4th Division as they stormed Mount Sabotino in 1916, a victory that would secure him a promotion to full General.

An Italian AA gun mounted on a truck on the Isonzo Front

Italian Army

Success at the 10th and 11th Battles of the Isonzo in 1917 would see Badoglio promoted again, and as a result he was a Lieutenant General in command of the XXVII Corps of the 2nd Army when the infamous Battle of Caporetto in late 1917. Here, as the Austro-Hungarian and German forces struck directly in the XXVII Corps sector, the Italian lines collapsed, resulting in a route for the Regio Esercito. Badoglio caught some flak for the defeat, although in the end it was the Chief of Staff, Marshal Luigi Cadorna, who received most of the blame and was dismissed from command, ending several disastrous years of his leadership.

Luigi Cadorna on the Isonzo Front

This removal stemmed from the fall of Prime Minister Paolo Boseli and his replacement with Vittorio Orlando, as well as pressure exerted by the other Entente Powers. In Cadorna’s place General Armando Diaz was placed in overall command, with Badoglio appointed Vice-Chief of Staff, despite his lackluster performance at Caporetto. Serving as an aggressive counterpoint to the careful Diaz, the Regio Esercito began to perform better in 1918, and in the fall of that year he played a role in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, wherein the defeat at Caporetto was avenged and the Austro-Hungarian Empire effectively destroyed. Badoglio was appointed to serve as a member of the delegation that negotiated the final Armistice with the collapsing Hapsburg Empire.

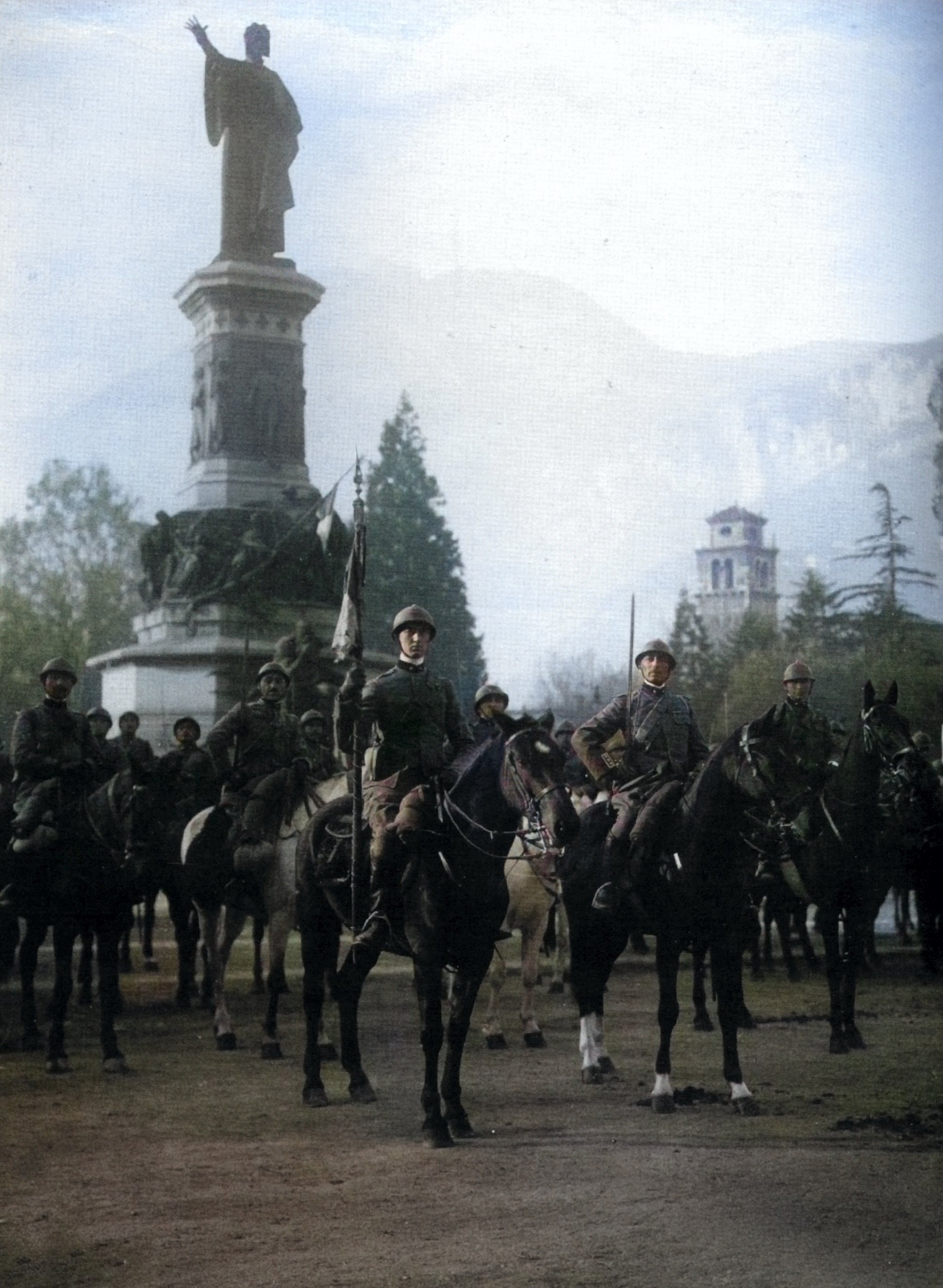

Italian cavalry in Trento after Vittorio Veneto

Italian Army

Following the victory in 1918 Badoglio replaced Diaz as Chief of Staff when the latter was named Minister of War in 1919, a post he would hold for just over a year, followed by serving on various missions abroad as a representative of the Italian Armed Forces.

Badoglio (front left) with other Italian officers during a 1921 meeting with US General John Pershing (front right)

In late 1922 the political landscape of Italy was changed dramatically as Benito Mussolini and his Fascists marched on Rome, and in the face of this crisis Badoglio was one of the officers called to meet with King Vittorio Emmanuelle III regarding the crisis. The general was of the opinion that the Fascists would be quickly dispersed by armed troops, and requested the Sovereign declare a state of emergency, empowering the military to put down the revolt. This was not granted, and Badoglio was shunted aside into an ambassador’s post in Brazil by the new Fascist government.

Benito Mussolini with his Blackshirts during the March on Rome

During his time abroad, the opportunistic general quickly came to embrace the new regime, and was swiftly rewarded for his faith. Recalled to Italy, in 1925 he was again named Chief of Staff of the Army by Mussolini, and in 1926 he was also named Marshal of Italy. Stepping down as Chief of Staff in 1928, Badoglio was appointed Governor-General of Italian Libya, which was at the time in a state of rebellion. Under Badoglio the Italian authorities responded with chemical weapons and large scale campaigns, resulting in the deportation of tens of thousands. When the leader of the rebellion, Omar Al-Mukhtar, was captured, he was executed on the Marshal’s orders, and by 1932 Badoglio reported to Rome that Libya had been pacified.

Badoglio (center) meeting with rebel leaders during an attempted parley in Libya

In 1935 Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, but the slow operations plan by the invasion’s commander, General Emilio De Bono, resulted in Mussolini installing Badoglio in his place. As he had in the Great War and in Libya, Badoglio happily deployed chemical weapons alongside the modern air and armored forces available to the Regio Esercito against the Ethiopians, and within a year the country was under Italian control, with Badoglio rewarded for his leadership with an appointment as the first Viceroy of Ethiopia and was awarded the title of Duke of Adis Ababa by the King. This would only be for a period of about two weeks, however, before he was recalled to Rome.

Badoglio (left) and de Bono in Massawa, Ethiopia

As the clouds of World War began to gather in the late 1930s Badoglio had some tertiary roles in the Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War as well as their annexation of Albania, in his post as Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces. As the Germans invaded Poland in 1939 he advised strongly to Mussolini that Italy was not ready for a major war against other powers, and set to making plans for the defense of Italy’s frontiers. When the Duce elected to attack France in 1940 as it fell to the Germans, Badoglio was ordered to invade with only three days of time to plan his operation. This resulted, predictably, in poor performance, with the collapsing French Army managing to hold the Italians just over the border.

Badoglio (standing at right) reads the Italian terms to French officers in 1940

The poor performance of the Regio Esercito in France, as well as late in their invasion of Greece in 1941, led to Badoglio falling from favor with the Duce, and he was replaced Ugo Cavellero as Chief of Staff. Disenfranchised with Fascism by this point, the Marshal returned home, essentially retired, and played no role as Italy lost its war in North Africa (during which his son was killed in action) and began to see increasing Allied air raids.

Badoglio during the Second World War

Despite this, he remained close to the King, and as the war deteriorated for Italy in 1943 Vittorio Emanuelle III made the decision to oust Mussolini, selecting Badoglio to replace him as Prime Minister, hoping that the Marshal would be able to ensure the support of the Grand Council of Fascism for the move. Ever the opportunist, Badoglio embraced the King’s appointment when the Grand Council issued a Vote of No Confidence in the Duce on 25 July of 1943, the King ordering the Marshal to form a government before even meeting with Mussolini.

Badoglio subsequently ordered the dissolution of the Fascist Blackshirt militia and its integration into the Royal Army, as well as the arrest of Mussolini. The National Fascist Party was itself disbanded, and Badoglio’s cabinet consisted of a number of military officers as well as members of various other parties. Badoglio did not, however, move to publicly end the war, wary of the large number of German forces by now in Italy to help fight the ongoing Allied invasion of the county, instead opting for a clandestine approach to the Allies in hopes of securing an armistice.

Italian soldiers are marched into captivity by their erstwhile German allies

An armistice was concluded between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies on 8 September, but a botched rollout of this news resulted in very few Italian units being aware they they were now on the other side as their erstwhile German allies moved to disarm the Regio Esercito. Despite significant forces available in and around the capital, the Marshal and the King elected to flee Rome on 9 September, moving south to seek the safety of Allied territory.

A meeting of the Badoglio Cabinet at Salerno in 1944

The group sailed to Brindisi aboard a Regia Marina corvette, as the bulk of the Italian Armed Forces collapsed without leadership as the Germans closed in. Eventually moved to Malta, the remnants of the Kingdom of Italy formally declared war on Germany on 13 October, 1943. In this post Badoglio was little more than a figurehead, with little popular support due to his association with the fallen Fascist regime. The King was likewise left with little support, and elected to transfer most of his powers to his son Crown Prince Umberto in June of 1944. With this change Badoglio was also replaced, with Ivanoe Bonomi taking office.

After the fall of his government, Badoglio retired from public office, returning to the village of his birth which had subsequently been renamed after him. In the aftermath of the war he managed to avoid trial as a war criminal due to the hopes that he would be useful in preventing the communists from taking control of Italy as the Cold War began, and indeed he was popular with the Italian right. Despite this, he would never return to public life, instead contenting himself with entertaining the occasional guest with a tour of his collection of war spoils in his villa. Pietro Badoglio died of congestive heart failure on 1 November of 1956, and the Marshal was provided with a state funeral. His villa was, according to his wishes, converted into a nursery school, which remained in operation until 1991.