Jimmy Doolittle

“The first lesson is that you can't lose a war if you have command of the air, and you can't win a war if you haven't.”

One of the greatest figures in the history of American aviaiton, James Harold Doolittle was born in Alameda, California on 14 December, 1896. Despite this, before reaching a year in age his father Frank had moved the family to Nome, Alaska, taking his wife Rosa and his infant son along three years later. Short and stocky, the young boy learned fast to defend himself, later reporting his first fight with another boy at the age of five.

Growing up in frontier Alaska was not easy, with young James needing to take a dogsled every day to fetch water for the family from a nearby pond in the winters. In another incident Doolittle would later recall a friend being killed by feral dogs when he fell on the way home from school. Experiences like this served to toughen the lad, while his prowess as a fighter led to no shortage of challengers and lending a taste for battle to him.

The scene on the beaches of Nome in 1899, which would leave a strong impression on Doolittle

Fearing the direction that her son was traveling, Rosa elected to move back to California in 1908 with the now eleven year old Jimmy, settling in Los Angeles. While here he would take up boxing under the tutelage of a teacher, and would eventually take the title of Amateur Boxing Champion of the Pacific Coast in 1912. Continued unsanctioned fights also continued, and eventually he found himself in jail for a weekend, his mother refusing to retrieve him. Another event during this time would also serve to change his life forever. In 1910 he would attend an event at the Dominguez Airfield near the city, which instilled a fascination with aviation, and with in two years he was building a hang glider with instructions from a magazine.

A biplane piloted by Glen Curtiss at the Dominguez Airfield Airshow in 1910, an event attended by a teenaged Doolittle

Graduating high school in 1914, Doolittle was by then attempting to win the affections of Josephine Daniels, a young woman who he himself would describe as being a polar opposite student, with her well mannered, studious nature at sharp contrast to the cocky young boxer. A proposal after graduation was rebuffed, leading the young man to head back to Alaska, hoping to make his fortune searching for gold with his father before returning as a more suitable candidate for a husband. This was short-lived, however, as little success and a strained relationship with his father would lead to Doolittle returning to California, now determined to get an education.

Doolittle started out at Los Angeles Junior College, boxing professionally in order to earn extra cash, using an alias to keep both Josephine and his mother from learning of it. Eventually transferring to the University of California Berkley, but before he started his senior year he enlisted in the US Army as the country entered the Great War in 1917.

Doolittle in Great War era uniform

Doolittle entered the service as a reserve officer in the Signal Corps, serving as an Aviation Cadet in October of 1917. After an eight week ground school, Doolittle proposed again to Josephne, this time successfully, taking a short honeymoon in San Diego, the couple so short on funds that they suvived on Red Cross Service Member’s canteens with free meals to soldiers. Shortly afterward Doolittle had his first flight, in a Curtiss biplane trainer in January of 1918. Despite witnessing a fatal crash as they taxied for takeoff, he successfully completed his flight, and would later solo after only seven hours of flight time. On 11 March, 1918 he graduated and received his commission, and despite a desire to be a fighter pilot he never made it to France before the Armistice of 11 November, instead remaining in the US as an instructor.

The end of the war saw large numbers of aviators and other servicemen mustered out, but Doolittle, with a wife to support and seeing a future in military aviation, elected to remain in the Army, with three other officers recommending him to be retained by the service, which was accepted.

Doolittle during his short refueling stop in Texas during his 1922 cross-country flight

Following this he would go on to create a reputation as one of the Army’s most daring, if perhap even reckless, pilots. In 1922 he set out to make the first cross county flight in less than 24 hours, and although an initial mishap delayed him for months, when airborne even severe storms could not stop the young aviator, and he won the Distinguished Flying Cross for this feat.

Not long afterward Doolittle was sent by the Army to attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, moving with his wife and two children to Boston for the September 1923 start of term. During his time at MIT he also set to exploring the limits endurance for both man and machine, pushing himself and his plane through extreme maneuvers, unlocking the secrets of G-force and publishing an academic paper on the subject that would earn him international acclaim as well as a second DFC. Within a year he graduated with a masters in science, and used his second year allocated by the Army to earn his PhD in Aeronautics, the first such degree awarded in the United States.

Doolittle with the Curtiss R3C Racer he flew to victory in the Schneider Cup Race of 1925

After his graduation Doolittle was selected by the Army to fly in the Schneider Cup, a seaplane race near Baltimore. On October 26, 1925, Doolittle took off in his Curtiss R3C Racer, managing to both beat the experienced US Navy pilots he was competing against as well as set a new world seaplane speed record. The accomplishment would win Doolittle the personal congratulations of both Army Air Service leader General Mason Patrick and Secretary of War Dwight Davis. His comrades back at McCook Field in Ohio, meanwhile, named him “Admiral” and paraded him around the base in a naval coat aboard a lifeboat on a truck bed.

This would also mark the beginning of a relationship between Doolittle and the Curtiss Aircraft Company, and in 1926 Doolittle was granted a leave of absence from the newly formed US Army Air Corps to travel to South America to fly demonstrations of the new aircraft offerings of the company. Thus it was that Doolittle found himself at the officer’s club in Santiago, Chile, where, aftter imbibing several cocktails, he attempted to perform a handstand on a window ledge. He suceeded, but the ledge crumbled, with the pilot sustaining two broken ankles. Not to be deterred, he had custom casts fabricated, allowing him to fly his demonstrations and impressing all who witnessed the feats.

A Curtiss P1 Hawk fighter, similar to that which Doolittle demonstrated in South America

During his convalescence at Walter Reed Army Hospital after his return to the US Doolittle selected his next challenge. It was commonly believed at the time that the maneuver known as an outside loop (a loop starting by diving the aircraft rather than climbing, as was commonly done) was impossible, with the forces involved being to much for both plane and pilot. In 1927 Doolittle once again board a Curtiss Hawk and performed the stunt, modestly claiming later that there was “nothing to it”.

Following another brief trip to South America Doolittle this time began to look toward experimenting on blind flight, using only instruments to navigate. Working with several engineers to develop new types of aircraft instruments, he set to work at Mitchell Field in New York. New, more accurate altimeters and an artificial horizon instrument were thus developed by Doolittle’s team, along with an improved bearing indicator. Doolittle himself performed the test flight, with a special canvas hood closed over the rear cockpit. The forward seat was occupied by a backup pilot without the hood, with his hands held over his head to prevent any impression that Doolittle was not in control. Again the flight was a success, marking the first time an aircraft had been taken off, flown and landed with only instruments.

Doolittle aboard his Consolidated Husky, with the hood used for instrument flying visible

Doolittle’s feat of instrument flying won him national notoriety as well as the congratulations and respect of many from across the aviation field. Despite this, in 1930 Doolittle made the decision to leave the Army, instead taking up a position with Shell Petroleum as director of its aviaiton fuel department. With illness effecting both his mother and mother in law, Doolittle would later cite that he was forced to do so in order to support them with the higher pay offered (Shell tripled his Army salary) in the private sector. Despite this he remained in the Army Reserve, and continued to race and set records, until he retired from the sport in 1934, disgusted by the media’s following of his children in hope of getting a picture of their reactions to his possible death.

Meanwhile, his efforts at Shell were directed toward the creation of a better aviaiton fuel, as he observed the USAAC falling behind other powers. He pushed hard for Shell to invest in the development of 100 octane fuel specifically for aircraft, and equally so for the cash-concerned Army leadership to purchase it. Tests in 1934 were a success, and by 1938 the new fuel was standard for the US Army in all its aircraft, solving the exisitng problems of a wide variety of types in service previously.

The USS Arizona burns after the attack on Pearl Harbor

As the international situation deteriorated in the late 1930s, Doolittle could see the writing on the wall: war was coming once again. He relayed his feelings to Army Air Corps leader Hap Arnold, and in 1940 requested to return to active duty. Arnold, for his part, was thrilled to see such an accomplished pilot back in the service, and approved the request immediately. Thus Doolittle was set to work, overseeing the massive expansion of US aircraft production for a war where air power had already proven decisive.

Everything changed on 7 December, 1941, when the Japanese demonstrated once and for all the value of air power when carrier based aircraft struck at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, devastating the US Pacific Fleet and forcing the nation into the conflict. Doolittle had missed his chance at combat in the First World War, but he was not about to miss this one.

One of Doolittle’s B25s practices a short takeoff at Eglin Field in Florida

In the aftermath of the attack one goal dominated the minds of President Roosevelt and other top US officials: launching a retaliatory strike on Japan at the earliest opportunity. A plan was hatched to use larger Army medium bombers, launched from Navy carriers. Arnold was brought aboard, and it was deceided that Doolittle, with his long experience and history of firsts and feats in the cockpit, was the best man for the job of organizing the ambitious operation. Doolittle set to work immediately quickly selecting the new North American B25 Mitchell as the best aircraft for the mission, with special modifications undertaken and volunteers raised to operate them on a mission so secret even they could not be told their destination.

Training took place at Eglin Field in Florida under Doolittle’s supervision, and by mid March of 1942 Doolittle flew to Washinton to meet with Arnold. Here Doolittle made a request to Arnold that he be allowed to lead the mission itself, rather than just its training. Arnold answered that it could be done, assuming that the Chief of Staff concurred. Thus Doolittle took off running, with the bemused Chief stating the equivalent of “if its OK with Hap, its OK with me”. The phone rang as Doolittle left the office, with the Chief being heard by a departing Doolittle to say “but I already told him he could go”.

Doolittle with his crew aboard the USS Hornet

Thus Doolittle led the flight of B25s as they crossed the US from Florida to California, using this last opportunity for training as they flew low and buzzed rooftops and farms. Upon arrival the planes were loaded onto the carrier USS Hornet, and set out with a small task force. It was only now that the crews were made aware that Doolittle was taking them to bomb Tokyo, the capitol of the Japanese Empire, a revelation that was met with excitement by both the airmen and sailors aboard. When the task force was spotted early, Doolittle made the call to launch, even though it meant they would not have sufficient fuel to make it to their planned landing sites in Free China.

Never a man to leave the danger to subordinates, Doolittle himself piloted the first of the sixteen B25s off of the deck of the Hornet as she pitched and heaved through a storm. For a moment it was thought that the Lt. Col. had crashed, before his bomber was seen to streak into the sky, passing over the ship as it came about.

Doolittle sits next to the wing of his crashed B25 in China

Doolittle and his four crewmates flew along at 200 feet, heading for the Emperor’s City. Alternating controlling the plane with his copilot Dick Cole, until they finally reached the coast of Japan after four hours of flight time. They came in from the north, the Japanese below unaware they were not a friendly aircraft, and as they entered Tokyo’s airspace Doolittle climbed rapidly to 1,500 feet and dropped his payload, while Cole reported being able to see the Imperial Palace from his seat next to Jimmy. Intense flak followed, but was innacurate. No interceptor appeared to molest them as they headed for China.

Aware that they would likely not reach the coast, the B25 crew donned their life jackets, but a tailwind allowed them to continue onward to avoid ditching over water. After thirteen hours of flight the fuel tanks were depleted, and Doolittle issued the order to abandon the aircraft. All bailed out into the stormy sky, and as he descended Doolittle worried about reinjuring his legs from the break in South America years before, but he landed softly in a soggy farm field. The sogginess allowed for a soft landing, but as it was due to being fertilized by fecal matter it was a mixed blessing to say the least. Eventually able to make contact with the Nationalist Chinese military forces in the area, and after initial suspician he was treated as a hero.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt decorated Doolittle with the Congressional Medal of Honor

After making his way out of China, Doolittle expected a court marshal for losing all of his planes, but was hailed as a hero at home. He was decorated with the Congressional Medal of Honor, as well as a promotion to Brigadier General, skipping the grade of full Colonel. He became a fixture of American war propaganda as one of the first high profile heroes of the new war, coming at a time when defeats on all fronts were causing Allied morale to sag significantly.

Doolittle poses with a recruitment poster

Original Color

Doolittle was promptly sent to North Africa to take command of the 12th Air Force, followed by a promotion to Major General in late 1942, and in early 1943 received a new command in charge of the North African Strategic Air Forces. In the end of the year he took command of the 15th Air Force and continued operations in the Mediterranean Theater, eeven flying missions despite the risks entailed.

Doolittle in England at the headquarters of the 8th Air Force

Doolittle received a third star in 1944, and took command of the massive 8th Air Force, tasked with the strategic bombing campaign on Germany from its bases in Britain. In this capacity he made the radical step of allowing the escorting fighters to separate from the bombers, resulting in them engaging and destroying the bulk of the Luftwaffe’s fighter forces before the Germans could even get close to the bombers. Thus freed, the fighters could increasingly be deployed as ground attack aircraft as the Germans lost the ability to mount large scale attacks on the raiding bombers. Strikes on German airfields and other targets by these fighters further crippled the dying Luftwaffe as 1944 went on.

Doolittle with other top US commanders in the European Theater, including Dwight D. Eisenhower and Carl Spaatz

By 1945 the Luftwaffe had been all but broken, and Doolittle’s 8th Air Force operated almost unmolested in the skies of Europe as Allied armies closed the vice on the Reich in the spring. By May Hitler was dead, and soon after the war came to an end. Doolittle and the 8th Air Force began to redeploy to the Pacific, but the capitulation of Japan at the end of the Summer negated their necessity, and thus the 8th never went into action against the Japanese. On January 6, 1946 Doolittle would retire into the inactive reserves, notable keeping his rank of Lieutenant General, a rarity in the service.

Doolittle at the 1947 Raider Reunion

After the war Doolittle would return to his civilian job at Shell, although he would remain active in the military, serving on various boards and commissions, as well as serving as an advisior to President Eisenhower and working in the intelligence community. He would also remain in close contact with the surviving Doolittle Raiders, including going to great pains to locate the missing airmen who had been captured by the Japanese, bringing back the four survivors and helping them to integrate back into the world after years of torturous captivity.

Doolittle sits in the cockpit of an F16 fighter during the 1982 Raider Reunion at MacDill Air Force Base

Doolittle fully retired from the military in 1959, having served as an advisor to the Air Force Chief of Staff as well as Chairman of the Board of Space Technology Laboratories. He remained an active member of the aviaiton community for the rest of his life.

In family matters, his two sons also served in the armed forces as officers, with the eldest, James Jr, being a fighter pilot who died in 1958 at the rank of Major, while John Doolittle retired as a Colonel. Doolittle lost his wife, Josephine, on Christmas Eve of 1988. Doolittle himself would die of a stroke on 27 September, 1993, being buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

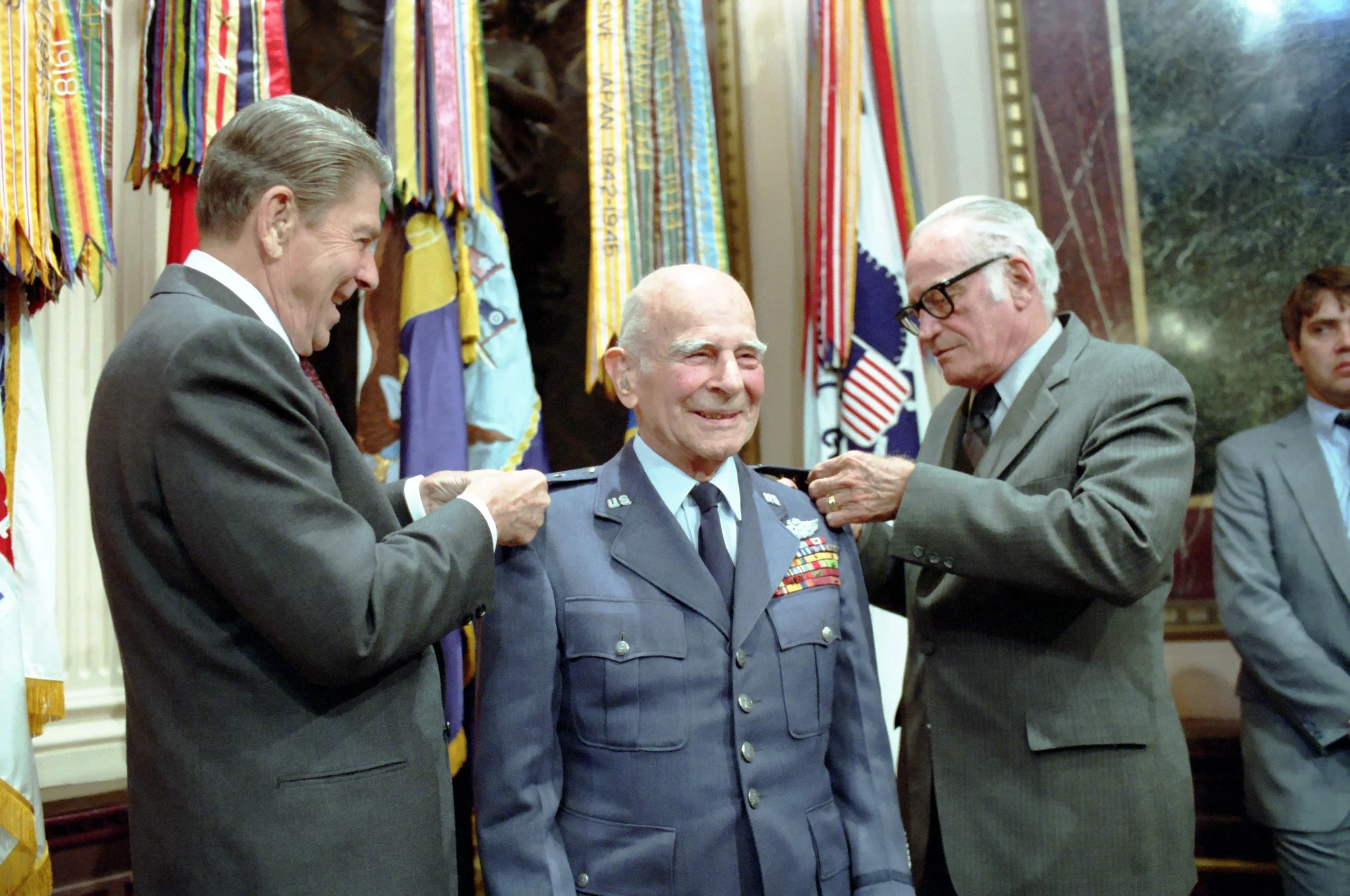

President Ronald Reagan and Senator Barry Goldwater pin Doolittle’s fourth star onto his shoulders in 1985

Jimmy Doolittle was one of the most famous officers in the history of American aviation. He held the Congressional Medal of Honor, along with two Distinguished Service Medals and three Distinguished Flying Crosses, as well as various foreign decorations. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1989 by President George HW Bush, and also received the Congressional Gold Medal posthumously in 2014 for his leadership in the Doolittle Raid of 1942. He was also given a fourth star with an honorary promotion to full General by President Ronald Reagan in 1985, with a special exception to regulations being passed to facilitate this.

Doolittle remains to this day a legenday figure in the annals of aviation history, in light of his acheivements and legacy both in war and peace.