The Aftermath

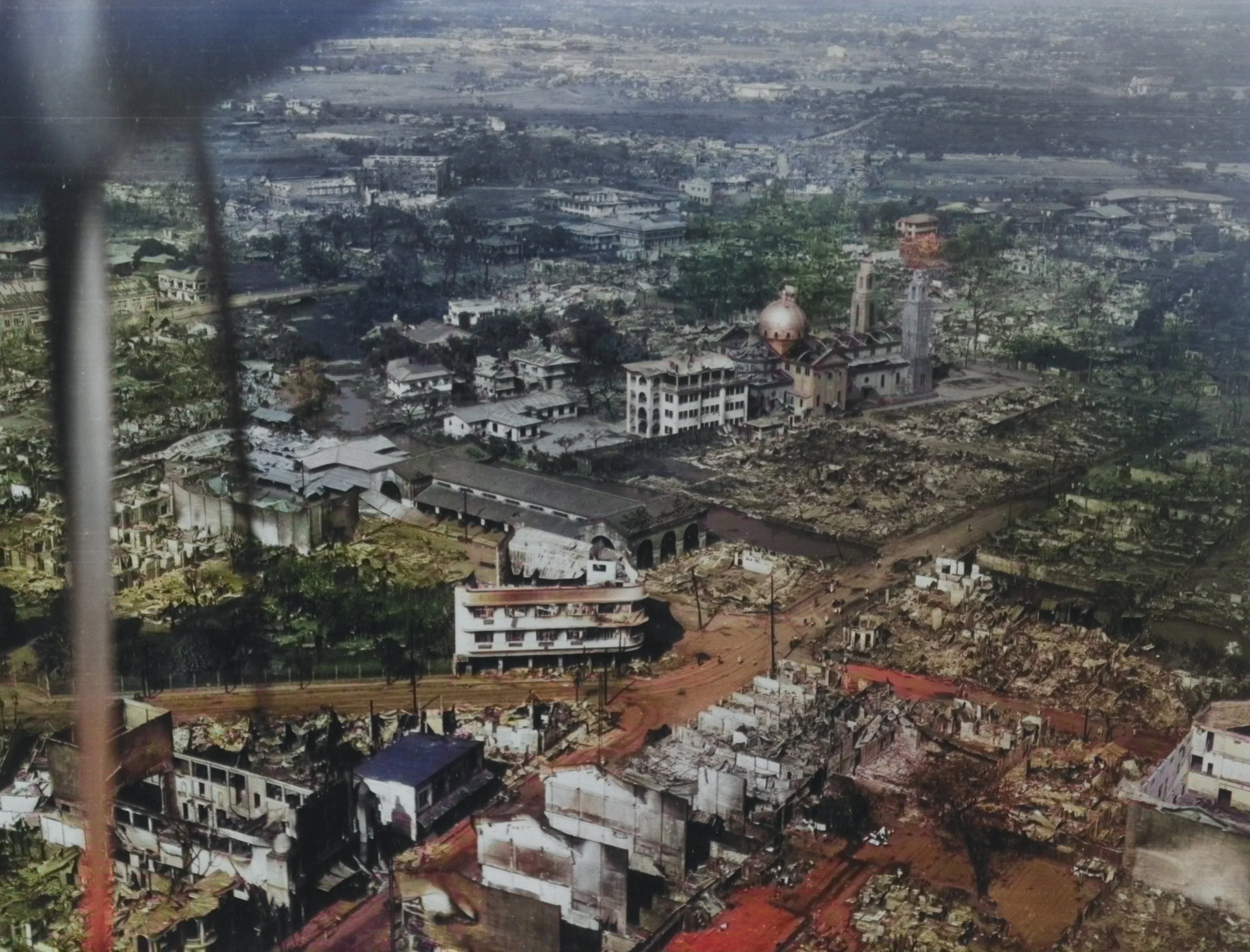

The wasteland that was once the bustling city center of Manila

US National Archives

The Battle of Manila had come to a close, but the war itself was not yet over. The Japanese had been pushed from the capitol, but Yamashita still had significant forces, especially in the north around Baguio, and had as much intention of surrender as the MNDF had. The Americans continued to push further into the mountains where Yamashita intended to make his stand, and the Japanese situation continued to deteriorate. The city of Baguio came under US artillery fire by the end of March, and the collaborationist government finally abandoned the Philippines entirely as President Laurel and what remained of his cabinet fled to Formosa.

General Yamashita under guard after surrendering to the US 32nd Infantry Division on Luzon

US Navy

Baguio would fall later in the spring, with the Japanese pushed even further back. Yamashita would continue to hold out in the mountains, even as the US expanded the campaign to the islands of Palawan and Mindanao in April. The American advance was relentless, but the Japanese managed to put up significant resistance, and when the war ended in August of 1945 Yamashita and his men were still fighting in northern Luzon. On September 2nd, 1945 Yamashita emerged from the jungle to surrender to the forces of the US 32nd Infantry Division, heralding the end of organized resistance in the Philippines.

Yamashita signs the document of formal surrender in Manila

US National Archives

The fighting in Manila Bay also did not end with the destruction of the MNDF in early March. Inside Fort Drum, a massive concrete structure built onto a rock in the bay looking much like a battleship made of concrete, the Japanese would remain defiant for some time. After a sustained bombardment both by sea and air the Americans managed to “board” the structure, with US combat engineers rigging a line into the ventilation to a waiting tanker, and after flooding the system with diesel fuel ignited it with white phosphorous, creating a massive explosion that destroyed the interior of the fort and the Japanese garrison, thus ending the last Japanese holdout in Manila Bay.

On August 17 of 1945 President Jose Laurel issued the final proclamation of the Second Philippine Republic, dissolving his government two days after the surrender of Japan. As the Americans began their occupation of Japan President Laurel was taken into custody on the orders of General MacArthur, who was now to serve as commander of the Army of Occupation. Charged with treason, he was held in prison awaiting trial until he received a pardon from President Manuel Roxas in 1948, and subsequently returned to politics after being elected to the Senate. Other officials of the Second Republic were likewise pardoned.

President Laurel and two of his officials are arrested by US troops in Osaka

Despite the end of Japanese resistance in Manila, the humanitarian crisis continued to exist, as the city’s remaining inhabitants were left without water, power or even shelter due to the terrible destruction wrought upon their homes. Disease was a serious threat as well, as medical services and even sanitation had broken down significantly, not to mention the huge numbers of unburied corpses strewn about the rubble. In order to combat the massive surge of the insect population the US Army Air Force began spraying DDT from C47s over the city, and massive labor crews toiled away to clear rubble and bury the dead. US Army engineers worked to repair blasted bridges and remove the landmines and other booby traps that still littered the city, and a commission on war crimes had been created, its members consisting of both military and civilian personnel tasked with interviewing survivors and documenting Japanese atrocities that had taken place in the city.

Almost a quarter of a million had been left homeless, many living in the open air under army mosquito nets. Food was almost exclusively from army distribution centers, which were only barely able to stave off starvation for such a huge population.

Also of note is the massive cultural loss sustained. The National Library and Museum’s collection was largely destroyed, along with it large numbers of artifacts and documents. The zoo was a broken ruin, its animals killed by artillery fire, and of course the Spanish architecture of the Intramuros was almost totally destroyed. The Pearl of the Orient had been reduced to an all but unrecognizable mess of twisted steel and pulverized concrete.

A C47 sprays DDT over the ruined streets of Manila

US National Archives

The people slowly began to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives, combing through the ruins of their homes, identifying the bodies of their loved ones when they could be identified. Many were buried in back yards, as the undertakers were so overwhelmed and the cemeteries so crowded. Others were buried where they lay, or cremated on the spot. In other areas, Army bulldozers dug mass graves, burying at least 8,000 in this manner. In Fort Santiago’s dungeons, the mass of corpses was too badly decayed to be moved, and they were cremated with flamethrowers. The stench of death permeated the battle scarred streets, reaching every inch of the city and leaving a horrid taste in the mouths of those residing there. There was no escape from the horror that had befallen the city.

A salute is fired after a burial in the American Cemetery at Fort McKinley

US National Archives

While efforts were made to dispose of American war dead with dignity, as well as with civilians, the sheer number of bodies made it difficult to do so quickly enough to stave off the health crisis that awaited in the putrefying flesh. To the Japanese no such courtesy was extended, with their men left to rot in the streets, sometimes buried in shallow unmarked graves simply to remove them from sight and for health concerns.

The utter devastation in the northern city

US National Archives

The dead were not the only crisis that the city faced either, as hospitals were still overwhelmed with wounded, and shortages of medical supplies were endemic. On average, almost 90,000 people checked into aid stations every day, and patients that had to stay sometimes had to sleep on pallets or even the open ground. In hospitals the situation was no better, with a lack of electricity and running water in many places, combined with overcrowding and the tropical heat to make for a truly miserable experience. The poor sanitary conditions had many fearful about epidemics breaking out, although thankfully none took place.

Yamashita arrives by ambulance at his trial

US National Archives

On August 19th, a delegation of Japanese officials had met with MacArthur in Manila to discuss the surrender of Japan before the official ceremonies in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. Also in the city was General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who was, by order of General MacArthur, to be tried for war crimes. He was held under guard inside the city, transported to the US High Commissioner’s Residence, now serving as the court, in a closed ambulance to prevent interference by the vengeful populace.

General Yamashita testifies at his trial in Manila

US National Archives

The trial moved quickly, with none of the judges having any legal experience, and was performed in a manner that makes it controversial to this day. The prosecution made their case that Yamashita failed to control his subordinates, namely Admiral Iwabuchi, and was thereby responsible for the Rape of Manila. Hearsay evidence and generous time allotments were allowed for the prosecution. His defense counsel put in a valiant effort to make the case that Yamashita had done all in his power to get Admiral Iwabuchi to withdraw, but failed, and Yamashita was pronounced guilty and sentenced to death. Appeals to General MacArthur and the Supreme Courts of both the Philippines and the United States and finally President Truman were rejected, and Yamashita hanged on February 23rd, 1946. His last words were of thanks to his American defense counsel.

The desire for revenge was palpable during the trial, as witnesses admonished Yamashita from the stand and guards had be posted to prevent a mob from lynching him. Despite this, over time the relationship between the Philippines and Japan has improved. In 1949 President Elpidio Quirino, whose family had been murdered in front of him during the battle for Manila, issued a pardon to all of the Japanese still imprisoned in the Philippines for war crimes.

The Japanese occupation had also signaled the end of the American era in the Philippines. After the war the Americans formally recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4th of 1946, leading the Commonwealth to be replaced by a Republic. The devastation wrought by the war has left the country to struggle to this day as the pre-war prosperity has proven difficult to restore, evidenced by the fact that the first State of the Nation Address issued by President Manuel Roxas in the new Republic was given in an old school rather than the once grand Legislature Building. A long hard road waited ahead.

On General Luna Street in the Intramuros a small plaza contains a memorial to the civilians who perished during the Battle of Manila. In the center a woman cradles her dead baby in her arms, whilst six more dead and dying people are seen around her. On the base is an inscription dedicating the monument to those lost in February of 1945:

“This memorial is dedicated to all those innocent victims of war, many of whom went nameless and unknown to a common grave, or never even knew a grave at all, their bodies having been consumed by fire or crushed to dust beneath the rubble of ruins.

Let this monument be a gravestone for each and every one of the over 100,000 men, women, children and infants killed in Manila during its battle of liberation, February 3 - March 3, 1945. We have never forgotten them. Nor shall we ever forget.

May they rest in peace as part now of the sacred ground of this city: The Manila of our affections.

February 18, 1995.”