Tuesday, May 27

The Death of Bismarck

The bridge of Bismarck from just ahead of turret Bruno in happier times (German Federal Archives)

The 27th of May opens with action, as Captain Vian’s destroyers engage the crippled Bismarck, charging toward the battleship with their torpedoes. Vian’s flagship, the HMS Cossack, was the first, taking damage and veering off before launching, followed by HMS Sikh and HMS Zulu, who all have a similar experience. The last ship, HMS Maori, is able to launch two torpedoes, as well as starting a fire on the deck of Bismarck with a star shell fired to illuminate the target.

“All of Germany is with you. Whatever can be done, will be done. Your sense of fulfilling your duty will strengthen our Volk in its struggle for survival. Adolf Hitler.”

At 0036 Admiral Lutjens received a response to his message from a few hours prior, in which the Fuhrer effectively bid farewell to the battleship. Meanwhile, Captain Lindemann ordered the the ship’s stores opened for the crew, and at 0258 Lutjens sends another message to Hitler:

“We will fight to the last, believing in you, my Fuhrer, and with unshakeable faith in Germany’s victory.”

Admiral Tovey in his office aboard HMS King George V (Royal Navy, original color)

Admiral Tovey knew that the Germans were all but helpless to avoid his ships, but also that they were far from disarmed. All of Bismarck’s formidable armament remained operational, and thus posed a serious threat to Tovey’s ships. At 0300 Captain Vian called off his attempts to engage the battleship with his destroyers, and set to shadowing Bismarck as they waited for the arrival of the big guns of Tovey’s battleships.

As the morning drew nearer, at 0351 another message arrives from OKM, this time awarding Korvettenkaptain (Commander) Adalbert Schneider, Bismarck’s chief gunnery officer, the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross (Germany’s highest wartime decoration) for the destruction of HMS Hood. Hours later, a message was received from close by, as U-556 continued to follow Force H, and attempted to vector U-47 to aid Bismarck, but the submarine was unable to make headway through the rough seas. The British were not through yet either, as HMS Maori attempted another torpedo run at 0700, although she was again driven off.

An AR196 about to be catapulted from the cruiser Admiral Hipper (German Federal Archives)

The mood on Bismarck was gloomy, as impending doom weighed upon the crew. Efforts began to get important information off the battleship, as the AR196 floatplane was loaded with the ship’s logs and war diary, to fly them to France. This fails, however, as the shell hit on the catapult area during the fight against Hood and Prince of Wales days prior, previously thought to be insignificant, prevents the launch of the aircraft. The heavy seas further precluded lowering it over the side to take off from the water, and the plane was pushed overboard, the full fuel tanks posing a hazard in the upcoming battle. A plan to transfer the logs to U47 likewise failed due to the heavy seas.

King George V sails to engage a target (Royal Navy)

As dawn approaches, Tovey’s battleships close in for the kill as the wounded Bismarck continues to circle. Tovey signals to Rodney:

“Am changing course to look for enemy. Keep station 1200 yards or more as you desire and adjust your bearings. If I do not like the first setup I may break off the engagement at once. Are you ready to engage?”

Rodney answers in the affirmative.

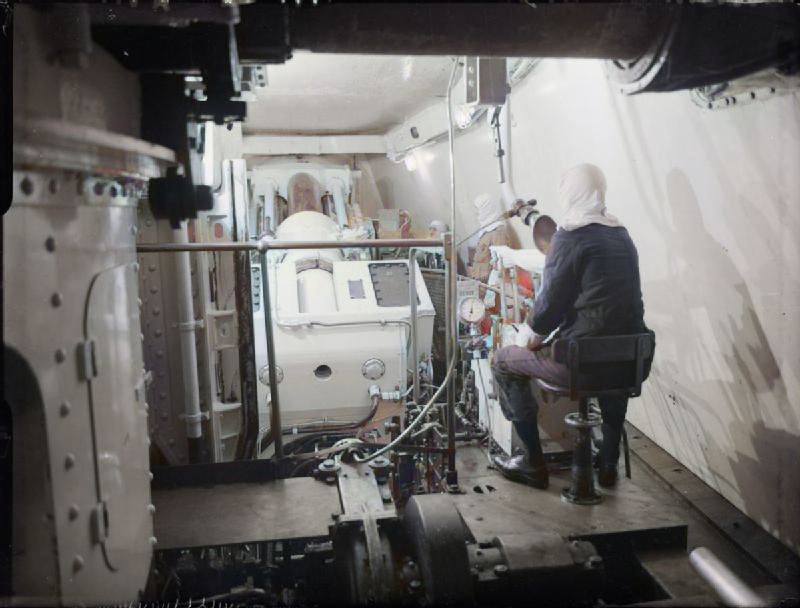

Inside a 14 inch main battery turret on King George V (Royal Navy

At 0722 the dawn breaks, with the greyish sunlight illuminating the sea, with the pride of the Kriegsmarine firmly in the sights of the Home Fleet. A message arrives from OKM that the Luftwaffe is scrambling all available maritime attack aircraft to assist the Bismarck, but there is no way they can arrive before the battle commences.

At 0737 the King George V and Rodney alter their course and increase to flank speed as they charge toward Bismarck.

The main batteries of HMS Rodney (Royal Navy)

The clock is ticking now, as Captain Lindemann is seen despondent on the bridge, lost in the inevitability of the destruction that awaits him. The first British ship they spot is the HMS Norfolk, the flagship of Admiral Wake-Walker which had dogged them since the Denmark Straight. Mistaking the German ship for Rodney, Wake-Walker flashed a recognition signal, but the answering flash was from Bismarck’s 15 inch guns, which missed but drove off the cruiser to wait for Tovey’s battleships.

A view of HMS Rodney’s bridge (Royal Navy)

At 0843 the announcement was blared aboard the Home Fleet battleships that Bismarck had been sighted. Men rush to make final preparations for battle, as Admiral Tovey and his crew don their steel helmets on King George V’s bridge. Men scrambled to action stations aboard the German battleship as well, as Bismarck prepared to fight her final battle.

“As imperturbable as though they were on their way to an execution, they were coming toward us in line abreast.”

Rodney’s guns firing (Royal Navy)

At 0847 Rodney opened fire with her 16 inch guns, the largest in this engagement, followed shortly afterward by the 14 guns of King George V. It takes a full minute for the massive 2,048 pound shells to land in the water near Bismarck. At 0850 the Bismarck replies with her forward batteries, straddling Rodney. The after turrets are not able to traverse enough to fire at the oncoming British ships.

King George V prepares to fire a salvo (Royal Navy)

Rodney is undamaged by the near miss from the German shells, but chaos reigns below, as the concussion from the massive guns firing has blown most of the lightbulbs in the forward compartments, bursting pipes and shattering bathroom fixtures. Meanwhile, King George V begins to suffer mechanical problems, although not as severe as her sister days prior.

HMS Rodney fires on Bismarck, which burns in the distance (Royal Navy)

At 0902 the Bismarck is rocked by hits from Rodney, smashing into the forward superstructure. The gun directors for the forward batteries are disabled, and the command bridge is hit, possibly killing Captain Lindemann and Admiral Lutjens. The proper firing solution now in place, the British ships, now joined by Norfolk, began to pummel the Bismarck with shells, turning to present their broadsides as they close, also opening fire with secondary guns.

Further hits destroyed the Bismarck’s main gun directors and disabled turret Bruno. Turret Anton soon followed, as the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire also joined the fray. As the ships passed to show their broadsides, the Bismarck still firing at King George V with her operational after batteries. Just as the aft directors get the proper firing solution, they are disabled, leaving the turrets to fire with only their own rangefinders.

Bismarck burns Royal Navy)

At 0925 the last blasts thundered from the forward batteries, as Turret Dora suffered a barrel explosion, peeling the huge steel barrel back like a banana. Turret Cesar continued firing until it too was silenced at 0931. Despite the destruction of her weapons, the battle flag still flew from the mainmast, and the British continued pummeling the dying battleship with shells from all sides. Most command and control functions have ceased aboard Bismarck, with individual crewmen and stations attempting to conduct their duties as best they can as their vessel is literally torn apart around them.

By 1000 the entire superstructure is an unrecognizable mass of twisted and charred steel. The massive German battleship is listing heavily to starboard, and is down in the stern, but still the British continue their fire. Fifteen minutes later another hit obliterates the bridge and sets it ablaze like a funeral pyre atop the wrecked superstructure, as flames and toxic fumes spread through the shattered ventilation ducts below decks. As the bombardment continues, First Officer Hans Oels abandons damage control efforts and orders every man for himself.

“Comrades, we can no longer fire our guns and anyway we have no more ammunition. Our hour has come. We must abandon ship. She will be scuttled. All hands to the upper deck.”

As the German sailors attempt to abandon ship those lucky enough to get on deck find a slaughterhouse as shrapnel whips across the broken planks, with many running blindly and falling through shell holes into fires burning below decks. In the ship’s canteen sailors trapped by a jammed hatch are freed when a shell blasts the hatch away, but a few seconds later another smashes into the compartment, tearing the men inside to pieces. In one of the magazine a fire is ignited, forcing the damage control crews to deliberately flood the compartment, trapping and drowning the men within.

By 1020 sailors are abandoning the sinking battleship as fast as they can as the ship now lists to port. Many in the water are killed when the heavy seas dash them against the steel hull, or when their dives off the side land on the torpedo bulkhead. Some would later report seeing the Luftwaffe aircrews from the AR196 committing suicide near the hangers.

At 1021 the British finally cease fire leaving the once proud Bismarck a mass of flame, shrouded in thick clouds of black smoke. As the remaining German sailors continue to scramble from their doomed flagship, the cruiser Dorsetshire is ordered to move in close. At 1036 she delivers the coup de grace, firing a salvo of torpedoes on the wreck of the Bismarck, which soon capsizes to port, his massive main turrets dropping away as he does so, and sinks by the stern.

Survivors are taken aboard the HMS Dorsetshire (Royal Navy)

As the survivors bob in the cold, oily water the sound of air escaping the sinking ship fills the air with a gurgling sound. The wounded begin to go under as their strength fails, and at least one officer shot himself as he floated in his life jacket. As the HMS Dorsetshire approached with the destroyer Maori the survivors began a scramble to their only hope for life, which meant an arduous climb over rope ladders with wet, oily hands as the ships rocked in the heavy seas.

At 1140 a lookout on Dorsetshire sights a possible submarine in the distance, and her captain is forced to make a terrible decision: he orders his ship to abandon the Germans after only rescuing 110 men. Their screams can be heard from the bridge, and crewmen below decks can hear them desperately banging on the full as the engines speed up. One British sailor even climbed down the ropes to help a wounded German aboard as the cruiser sped up, risking being left behind in the process. Three more would be rescued from a raft by U-74, and another by the German weather ship Sachsenwald, but further efforts by the Germans and by the neutral Spanish cruiser Canarias are fruitless.

Bismarck took 2,135 men to the bottom of the Atlantic with him, including Captain Lindemann and Admiral Lutjens. Efforts to find the logs that had been cast into the sea by U-74 and U-556 proved unsuccessful, and they have been lost to history. The failure of Exercise Rhine had a profound effect on Hitler, who expressly forbade any further Atlantic operations by surface warships. His hopes of cruiser warfare quashed, Grand Admiral Raeder eventually falls from favor, replaced with Karl Donitz, who moves the Kriegsmarine into an entirely U-boat centered strategy for the duration of the war.

Exercise Rhine became one of the most celebrated naval episodes of the Second World War, and of all time. The 1960 film Sink the Bismarck! is regarded as a classic despite some innacuracies, and the hit country music song Sink the Bismarck by Johnny Horton helped to cement the events of May 1941 into popular memory. To this day the wrecks of HMS Hood and KMS Bismarck lie in the cold blackness of the Atlantic, tombs for the thousands of sailors who had crewed them into history.