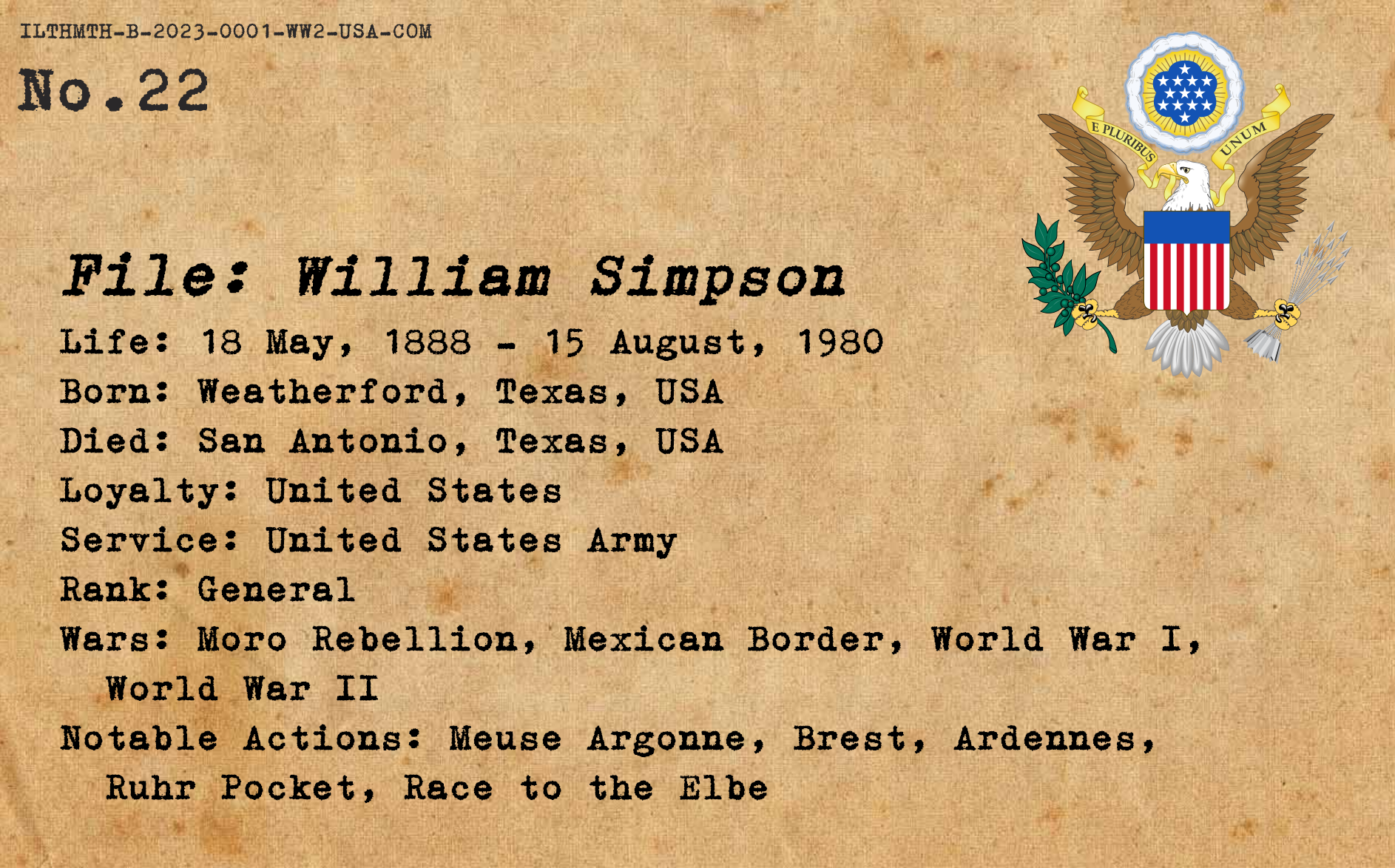

William Simpson

“Never Send an Infantryman Where You Can Send an Artillery Shell”

Born the son of a rancher in Weatherford, Texas in 1888, William Hood Smith was raised on the family ranch in Aledo, Texas. There he was regaled with his father’s stories of his time serving in the Confederate Army under cavalry general Nathan Bedford Forrest, along with those of Indian raids on the frontier community in the mid nineteenth century.

Schooling did not begin for Simpson until the age of eight, when he began to ride a horse in to class every day, and although he demonstrated athletic prowess his academic abilities were considered average at best. Desiring a career in the military, he was able to gain a place at West Point through Texas Governor Samuel Lanham, an old friend and law practice partner of his grandfather. Despite his earlier performance, he was able to pass the required entrance examination, entering the Academy in 1905 at the age of 17.

Simpson in his West Point graduation photo

In 1909 Simpson graduated from West Point, managing to place 101st out of the 103 in his class, which also included the likes of George S. Patton and Robert Eichelberger. The newly minted Lieutenant then transferred to the Philippines, serving with a unit combatting the ongoing Moro insurrection there before returning to the United States to command a unit assigned to General Black Jack Pershing’s expedition to hunt down Pancho Villa in Mexico in 1916.

When the US entered the Great War in 1917, Simpson received a promotion to Captain, eventually serving on the staff of the 33rd Division in France, and was a Major serving as assistant Chief of Staff for the division when the Armistice was declared in November of 1918. He would become and acting Lt. Colonel just afterward, taking over as Chief of Staff at that time as well.

US officers in an observation post during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of 1918

During the Interwar Period Simpson would serve in a variety of posts across the United States, and would marry in 1921. He attended the US Army War College, an by the time the Second World War began was a Colonel serving as an instructor there, by now gaining a reputation as an excellent organizer and trainer.

A promotion to Brigadier General came in 1940, along with a posting as commanding officer of the 9th Infantry Regiment before being reassigned to command the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Camp Wolters, Texas. In October of 1941 he took command of the 35th Infantry Division with the rank of Major General, and it was during his tenure there that the United States would be drawn into the Second World War after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

General Simpson at his desk at Camp Wolters

University of Texas - Arlington

Simpson would subsequently serve as a corps commander and eventually command the US 4th Army during its training, reaching the rank of Lt. General by mid 1943. Eventually this force was activated for service in Europe, and redesignated as the 8th Army. Simpson would follow them, flying to Britain in May of 1944 to meet with the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Simpson had been a classmate of Eisenhower at the War College, and although their interactions had been limited “Ike” had actually requested that Simpson be posted for a combat command in Europe, along with General Courtney Hodges. Simpson was thus called to St. James College to attend a briefing by the top Allied commanders regarding the upcoming Invasion of France, in which Simpson’s forces (redesignated 9th Army to avoid confusion with the British 8th Army) would take part.

An M18 Hellcat tank destroyer supports GIs on the streets of Brest

Simpson himself, along with his staff, were present in France by July of 1944, although the 9th Army itself was not able to enter combat until September, when it was ordered to attack the port city of Brest. It was here the Simpson deployed the strategy that would become his hallmark: massive use of overwhelming firepower in order to prevent casualties on his side. This was effective, although the toll on the city itself was severe by the time the German garrison surrendered on 20 September.

Simpson (at right, wearing helmet), inspects the Siegfried Line with Winston Churchill and Bernard Montgomery

Following this, Simpson and the 9th Army moved eastward toward Germany with the advancing Allied armies, eventually engaging the vaunted Siegfried Line near Aachen, pushing through as far as the Ruhr River. When the German offensive in the Ardennes comenced in December the 9th was placed under the command of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group as they found themselves separated from other US forces. Holding their line along the Roer, the 9th remained in position, as the German “Bulge” was reduced over the following month.

Stalled at the Roer due to the Germans destroying the dams upriver, Simpson and the 9th Army held their positions until late February, when they formed the southern component of a large pincer maneuver with the Canadians, meeting them on 5 March along the Rhine. This operation would earn Simpson a spot on the cover of LIFE Magazine, appearing along with a story about the success of their operation.

The Rhine was crossed on 24 March, as a component of Operation Plunder, with Simpson crossing the river aboard a landing craft in the company of Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Montgomery (who issued a personal commendation for the 9th Army’s effectiveness). This was followed by a race across western Germany as the Wehrmacht collapsed, with the 9th Army’s 2nd Armored Division and 83rd Infantry Division reaching the demarcation line on the Elbe to wait for the Soviets on 11 April. Other forces were dispatched to aid in the destruction of the German forces trapped in the Ruhr Pocket, which was completed by 21 April.

Simpson joins Monty and Churchill on a bridge over the Rhine

As the sounds of battle in nearby Berlin could be heard from 9th Army positions at Magdeburg on the Elbe, a swarm of refugees, both military and civilian, appeared at the destroyed bridge at Tangermunde. Simpson had put in a request to Eisenhower for permission to drive on the German capitol before the Soviets encircled it via the intact autobahn, but had been denied. Later, as Soviet shells began to land amongst the crowds on the eastern bank, Simpson ordered his men to pull back to avoid friendly fire, thus also allowing refugees and surrendering German troops (who the 9th had orders not to admit) to cross to the American controlled western bank.

German soldiers cross a destroyed bridge over the Elbe to surrender to the men of the 9th Army

In total, about 100,000 German soldiers were captured by the 9th Army as they streamed over the Elbe before VE Day. Simpson and his men were subsequently assigned to occupation duty as other US forces were redeployed to the Pacific in anticipation of the coming invasion of Japan, until they too were sent to China in June. Simpson was to be named Deputy Theater Commander, but the collapse of Japan in August prevented this from coming to be.

Simpson (far left) poses with other senior officers after arriving in China

US National Archives

By the end of 1945 Simpson was back in command of forces stationed within the United States, retiring in 1946. A popular commander of his men, his old friend Eisenhower would later call Simpson “the type of leader the American soldier deserves”, and his reputation as a stoic commander and organizer followed him out of the service. He was promoted in retirement to full General in 1954, while he lived in San Antonio. He would work as a bank executive after his retirement from the Army, and he was also active in various veteran’s organizations as well as children’s charities.

After the death of his wife in 1971 Simpson would move into a hotel in San Antonio before remarrying in 1978, with the now 90 year old General marrying a 57 year old retired government employee. They built and moved into a new home in the suburb of Windcrest shortly after, and Simpson died at Brooke Army Medical Center two years later, on 15 August, 1980. He was subsequently buried in Arlington National Cemetery, alongside his first wife, Ruth.