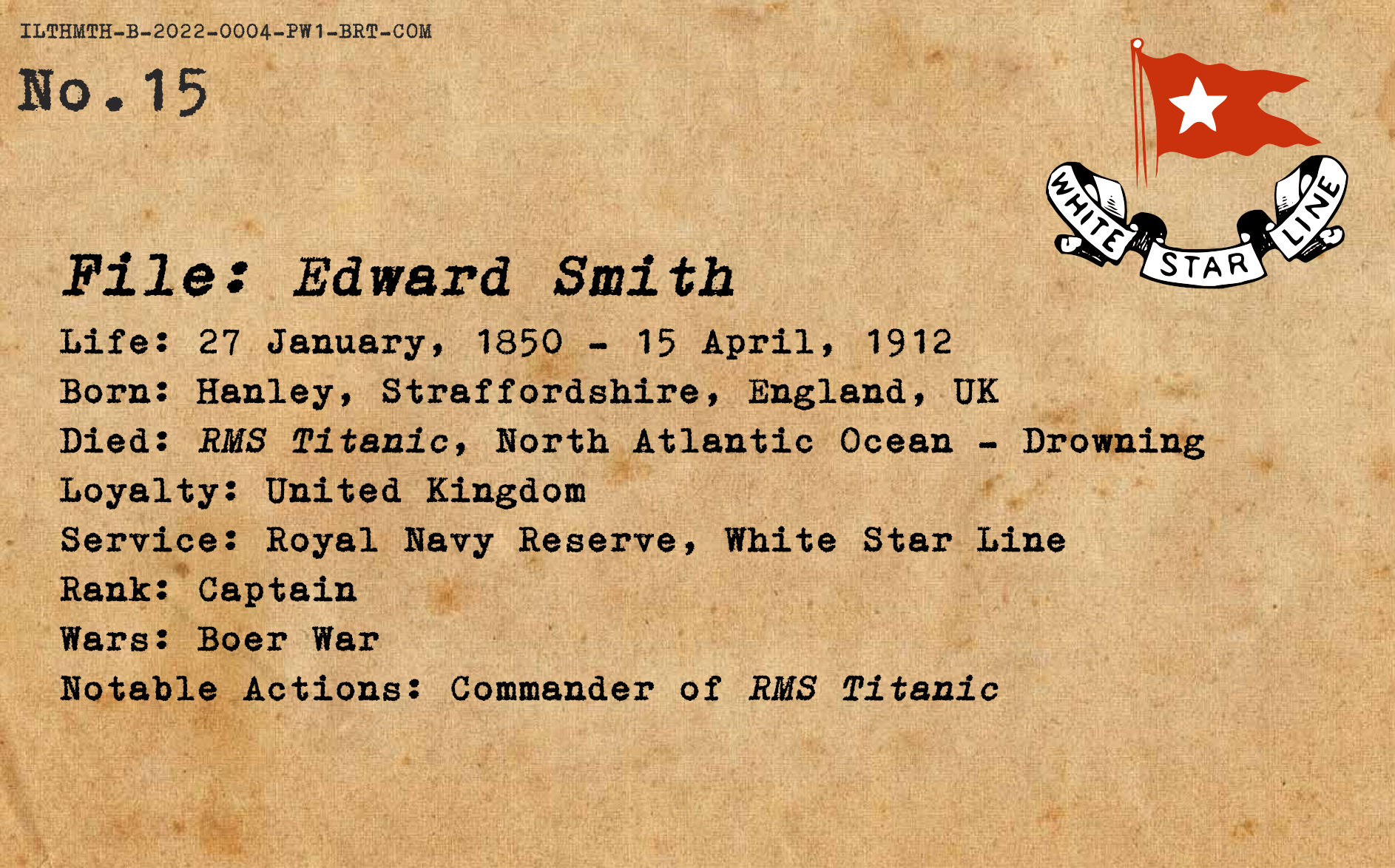

Edward Smith

“When anyone asks me how I can best describe my experience in nearly forty years at sea, I merely say, uneventful.”

Edward John Smith was born to John and Catherine Smith in the English town of Hanley on 27 January, 1850. His father worked as a potter, and eventually his parents went into business together, opening a shop as their son attended a local school until, at the age of twelve, he left school to take on a job in a factory before signing on as a sailor aboard the packet ship Senator Weber in 1867 at the age of 17. His older half brother, Joseph Hancock, was by this time a captain, and helped to facilitate his younger brother’s entry into the sailing profession. The desertion of several of the ship’s company after arriving in California at the end of Smith’s first voyage led to Captain Hancock having no choice but to promote his brother to Third Mate, and thus Smith’s career as an officer began in earnest.

The White Star liner SS Britannic

By the late 1870s Smith had risen to command his own ship, but this would not be the end of his career. In 1880 he would see and become interested in the steamer SS Britannic, and this would spur him to give up his command to join White Star, entering service as Fourth Officer aboard the RMS Celtic. he would once again begin climbing the ladder to command, and reached his goal in 1887 when he took command of the RMS Republic for a short period. That same year he would marry Eleanor Pennington, with whom he would have a daughter, Helen Smith, in 1902.

The next year, in 1888, he took command of the older four mast steamer RMS Baltic, and from thence would move between several commands. It was during this time that Smith began to foster a relationship with both passengers and crew, as well as company executives such as Bruce Ismay, which would have a bearing on his later career.

The RMS Majestic, Smith’s first major command with the White Star Line

His first major command would come in 1895, when he captained the RMS Majestic, then one of the premier liners of the White Star Line’s fleet. He would hold this command for almost a decade, and during this time the British Empire would become embroiled in the Boer War in South Africa. Smith was an officer in the Royal Navy Reserve, and the Majestic was likewise a reserve ship in the Queen’s fleet. Smith and the Majestic saw service ferrying troops to Cape Colony, making two trips with no problems, with Smith being awarded the Transport Medal with the South Africa Clasp for his service in the conflict.

Captain Smith in 1895

Smith left the Majestic in 1904 as the ship went in for a refit, and for the first time took White Star’s newest liner on her maiden voyage. The new RMS Baltic was a far cry from the old four masted steamer Smith had commanded earlier in his tenure. The largest ship in existence at the time, she was one of White Star’s so called “Big Four”, intended to be both the largest and most luxurious ships in service. The maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York passed without incident, and he would eventually stage a repeat performance as he commanded RMS Adriatic on her maiden voyage, again without problems. During his tenure aboard Adriatic he would cement his place as “The Millionaire’s Captain”, being often photographed and even interviewed in major newspapers.

RMS Olympic arrives in New York after her maiden voyage, with Smith in command

In 1911 another liner entered service with White Star, again taking the title of largest and grandest ship in the world. She was the RMS Olympic, and once again Smith would take command as her captain for her first crossing. This was again successful, and Smith was on hand as the liner was opened for public tours after docking in New York. She would make several subsequent crossings without incident, up until her fifth crossing.

The damage to the hull of Olympic after her collision with HMS Hawke

On 20 September, 1911, as Olympic steamed through the Solent, the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Hawke collided with her, opening a large hole in the liner and crumpling the bow of the warship. Smith was on the bridge during the incident, and the subsequent Royal Navy inquiry placed the blame on Olympic, although they specifically absolved Smith of liability. The result was that Olympic was out of service until November, and Smith resumed command, a post he held until March, when he took command of yet another brand new liner.

RMS Titanic departs Southampton on her maiden voyage

On 1 April, 1912 Smith boarded the new RMS Titanic, the sister of Olympic, in Belfast, sailing to Southampton on 4 April. He took with him his Chief Officer, Henry Wilde, bumping the chain of command down for the rest of Titanic’s officers in the process. He returned home for a short period following, awaiting sailing day on 10 April. With boarding and final inspections complete, the world’s largest liner departed at noon.

The steamer New York almost hits Titanic as she leaves Southampton

As the massive new liner steamed for the harbor entrance, the wash created caused the liner SS City of New York to break free from her moorings, her stern swinging out to hit the Titanic. The quick actions of a nearby tug and Captain Smith on the bridge averted a collision by mere feet, and the Titanic continued toward the open sea.

Captain Smith looks down from Titanic’s port bridge wing

After leaving Southampton, Titanic steamed southward across the English Channel, where she took on passengers at Cherbourg, subsequently heading north again to stop at Queenstown, Ireland before departing for New York over the Atlantic in the afternoon of 11 April.

Titanic steams with assistance from tugs

As Titanic steamed westward she encountered fair weather, although temperatures remained cold, along with increasing reports of ice as the voyage continued. Smith and his officers performed a daily inspection of the ship, joined by members of the Guarantee Group, comprised of personnel from Harland and Wolfe, the ship’s builders. He spent evenings in the First Class Dining Saloon on D-Deck, where he entertained passengers at his private table. He was often joined her by Bruce Ismay, Chairman of the White Star Line and a passenger for the maiden voyage. On Sunday, 14 April, Smith led an interdenominational worship service in the First Class Dining Saloon, and as the day progressed even more reports of ice were received by the ship’s wireless operators.

Captain Smith on Titanic’s boat deck with Purser Hugh McElroy

On the evening of 14 April Smith retired to his quarters, leaving First Officer William Murdoch in command on the bridge. At 2340 (11:40PM) the lookouts on the forward mast reported to the bridge they had sighted an iceberg directly in the path of the liner, and Murdoch attempted to maneuver the ship to avoid it. This failed, and the ship hit the iceberg, causing flooding in several forward compartments. The disturbance roused Smith, who arrived on the bridge just after Murdoch closed the ships watertight bulkheads.

Smith issued orders for the ship’s carpenter to perform a damage inspection, who he joined in the lower decks of the liner. The outlook was grave, and just after midnight issued orders for the lifeboats to be uncovered and swung out, with orders issued also to the wireless operators to begin issuing distress calls.

Survivors of the Titanic photographed aboard a lifeboat

During the ensuing evacuation Captain Smith’s actions and eventual fate remain unconfirmed to this day. Some reports show an indecisive response, led instead by his subordinates. Others show him taking a more direct role in the evacuation. He is often cited as attempting to recall the underfilled boats to the sinking ship, and various other reports also place him as moving about during the evacuation, remaining in command until the end. His last official act as Captain was to release his crew from their duties as the Titanic began her final plunge into the depths of the icey North Atlantic.

He was last seen as the bridge went under, with varying accounts reporting he was seen diving into the sea or remaining on the bridge as it submerged. Some survivors also reported him in the water near the overturned Collapsible Lifeboat B, but he swam away and was not reported again. Some reports also exist that he committed suicide, but these were sharply refuted by both survivors and Captain Rostron of the rescuing ship RMS Carpathia.

The bathtub in Captain Smith’s quarters on the wreck of the Titanic, now gone as the wreck deteriorates

Original Color, US NOAA

There remains debate regarding Smith’s actions and how they might or might not have contributed to the infamous disaster in April of 1912. Some point out his decision not to slow the ship due to ice warnings, while others point to his absence from the bridge at the time of the collision. Both of these can, of course be explained away as standard procedure, but debate continues. In addition, his handling of the disaster itself has been called into question, including those accounts that he was mostly absent during the evacuation of the ship and the mystery of how his life came to an end. Despite all of this, he remains a popular hero of the disaster, with his famous image being the archetypical sea captain, ready to go down with his ship.